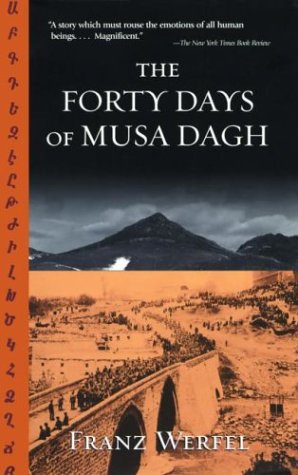

A Genocide Literature Classic: The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, Franz Werfel

By Matt Hanson

I bought a worn copy of The Forty Days of Musa Dagh for $1.10 from a walkup used bookstore in New Bedford, Massachusetts, the old glory of American fishing ports where Herman Melville set sail to write Moby Dick during the industrial city’s heyday when oil money meant the blood of whales. The junk-shooting, painkiller-popping populace has since drunk and bled its nostalgic local economy dry under the noir-stained, 19th century lampposts and ship-building mills that once hosted the likes of the abolitionist leader Frederick Douglas and a then-unknown Abraham Lincoln.

The storied literary shop, in fact, is called Upstairs, down a side street around the corner from the historic drag of Union Street, and fronted by a very thin and most eccentric middle-aged, irreligious Jewish man named Ira whose encyclopedic grasp of his bulging, towering shelves is only less incredible than the strength of the cracking, musty, dusty floorboards. Like a wise recluse, he sits faithfully behind his cluttered desk piled high from the ground with tomes that surpass all sense of secondhand, or thirdhand use, having, by appearances, passed through more hands than that possessed by the Hindu god Shiva.

I had returned there, to my childhood stomping grounds, from Istanbul, and walked up to the obscure, dark treasure trove I had known and loved with my bookish factory worker of a Manhattan-born Greek Jewish grandfather whose parents were Ottoman subjects. I eyed the thick, brittle spine of Franz Werfel’s best-known classic, a book that continues to set off sparks in the ongoing conflict to reconcile Turkish and Armenian wartime traumas unfaded by over a century of epochal paradigm shifts.

The lingering cackle of the dead Ottoman Empire now echoes in the highland valleys of Hatay, a curious patch of land that was once a republic of its own, now bordering Syria in Turkey’s furthest eastern Mediterranean region. It is where the real-life Musa Dagh stands, some thirty kilometers from Hatay’s capital of Antakya (to philhellenes, Antioch). The name literally means “Moses Mountain” from the Turkish. It is where Werfel framed his novelization of the first genocide in the 20th century, the systematic killing of 1.5 million Armenians in 1915. The historical context, still politically sensitive in Turkey, has very recently renewed its stamp as a fact for the records in a new way, confirmed with cold, hard documentary evidence last year by the Turkish historian Taner Akcam at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. Akcam has been compared to Sherlock Holmes for his detective work uncovering the clues to cement the case that acts of genocide were indeed committed by, among a number of suspects, the Ottoman official Behaeddin Shakir. Akcam deciphered a telegram kept in the Armenian Patriarchate in Jerusalem, showing that Shakir was not only implicated in the genocide, but that he was convicted of his crimes in a military tribunal, only to flee the country for Berlin, where he was gunned down by Armenian assassins in 1922.*

That it was wartime is not an excuse, although it is a common rebuttal, one quickly overturned by the obvious reality that Hitler ordered the final solution in WWII. Armenian genocide denial, as it should be termed, to parallel the conspiratorial leagues of Holocaust deniers, has no footing in today’s world. And yet, by all accounts, Werfel’s story, while certainly a very loud canary in the coal mine for burgeoning genocide awareness in Europe, bears only slight resemblance to the facts, despite his eyewitness research. Still, that does not overshadow the enduring political impact of its paradigm-shifting publication.

The siege that pivots the narrative, when eight hundred families of brutalized Armenian deportees huddled among kin who defended themselves against the Ottoman army in 1915, had lasted for only 36 days. The number 40 is mythic, biblically comparable to the duration of the Egyptian exodus of Moses and the Israelites on route to the Promised Land. Werfel’s story is, at its core, a character study of the effects of Europeanisation on the assimilated, Armenian-born protagonist, Gabriel Bagradian, who arrives to eastern Anatolia to see his childhood village in the shadow of Musa Dagh with his French wife Juliette and son, Stephen, in tow.

Bagradian first overhears talk of the infamous deportations that amounted to what is now known as the Armenian genocide in a bathhouse shared with Turkish officials. A venerable Muslim elder, Agha Rifaat Bereket, verifies the terrible truth. He then learns of the arrests and executions of Armenians in Istanbul from a local priest, Ter Haigasun. When he finds a store of rifles in a cemetery, plans for local resistance begin, and the villagers soon volunteer. Bagradian’s young family defy evacuation efforts for them to return to Paris, and they soon find themselves on the mountain summit in the company of traumatised, colourful country folk that Werfel painted liberally with his knack for theatrical characterisation.

His firsthand experiences on the front lines of WWI were fuel to the fire of the book’s incendiary war scenes, rife with intricate stratagems on the field of battle, strengthened by his keen eye for the details of the tactics, equipment and arms used by the armed resistance and Turkish forces in the region at that time. They rallied with Austro-Hungarian 10 cm howitzers, deployed catapults that could launch boulders to repel advancing enemies below the high ground, and when at wit’s end and rations ran deathly thin, prepared an emergency signal fire.

The exotic setting continues to fire the imaginations of readers from the ends of the scarred lands of Anatolia to the salons of Europe and to the world beyond, as it had when The Forty Days was published under a bad sign in 1933, coinciding with the rise of Nazism. Such works of liberated humanism, in every form of expression, were blacklisted as degenerate by Hitler and his racist, so-called national socialists, during a regime that would come to emblazon the facts of genocide on the front page of modern history.

Germany’s infamous book burnings had already turned many of Werfel’s titles to ashes, and his new release, about war crimes in the Near East, only stoked the flames, although many brave booksellers kept it in stock for as long as they could, until February of 1934. When the Third Reich’s aryan supremacy inferno finally cooled, literary historians saw The Forty Days as profanely prophetic, as Werfel’s cautionary tale likened the Holocaust’s deadly deportations with the suffering of Anatolia’s bygone Armenians. The legacy of its censorship has sadly lived on, unjustly sidelining the all-but-forgotten masterpiece of early 20th century literature in the lands where the exposure of its story remains relevant.

Attempts to put a stranglehold on Werfel’s fictional narrative began immediately, when Turkish diplomats petitioned the Nazis to ban The Forty Days before its publication, going so far as to intimidate the multigenerational Armenian and Jewish families of Istanbul into silence, coercing them to public disapproval over its content.** Nowadays, lobbyists like ASIMED (Struggle Against Baseless Allegations of Genocide) are active in Turkey, from where they have managed successful campaigns to thwart several attempts to film the novel. Politicised road blocks were set up as soon as 1934, when MGM sought Clark Gable to play the lead, but even the muscly Sylvester Stallone was no match during his 2007 production talks, nor crazy-eyed Mel Gibson, when he considered the project around 2009.***

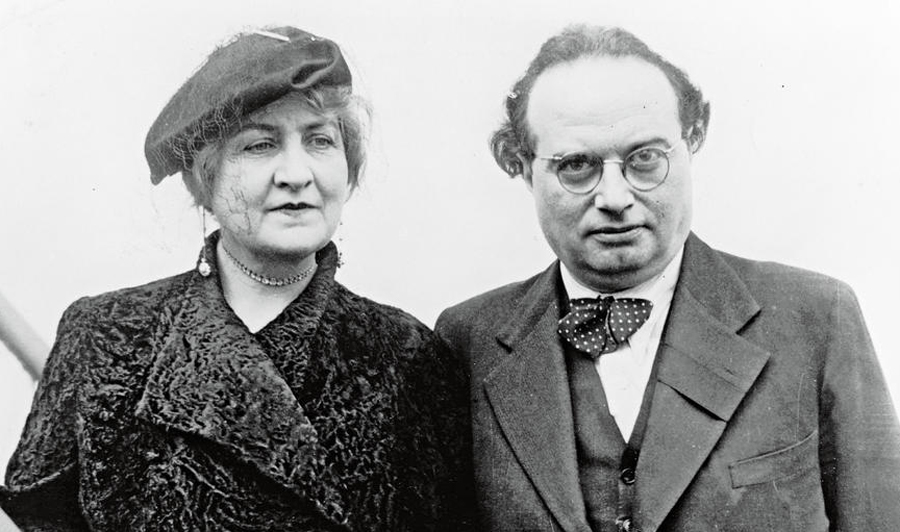

Equally praised as an important playwright and poet, Werfel is remembered as one of the leading men of letters in pre-Nazi Austria who started out by rubbing shoulders with Franz Kafka and Max Brod at the Cafe Arco, where they enjoyed highbrow intellectual comradeship forming the Prague Circle of Jewish Writers. Later in Vienna, after suffering an injury in WWI, he was a regular patron at Cafe Central, accompanying Robert Musil and Franz Blei, who introduced him to the widow of Gustav Mahler, a talented woman named Alma, who is survived by almost equal renown as a composer.

Alma was eleven years older than Franz, and she demanded that he renounce Judaism to be with her, which he did, a la the romance of secularism, pronouncing universal love as the great unifier and ultimate point of life and all religions. The filmmaker Milos Forman, another great Czech artist, said it best while playing a Catholic priest in Edward Norton’s 2000 film, “Keeping the Faith”, that to be a loyal spouse, or a celibate priest, is the same challenge. As the global depression introduced the ‘30s, Werfel’s life behind the raucous theatre as a dramatist increasingly waned in favor an occasional quiet reading at the bookshop as a more private man given to the writing of novels.

The book that gained him enduring international fame was his third novel, sometimes translated simply as The Forty Days, and eventually into 24 languages. It was a proud, international success, bestselling 125,000 copies in four months in the U.S., as it went on to become a Book-of-the-Month Club selection in 1935. It was preceded by his 800-page critical achievement, but popular failure, “The Pure in Heart”, which chronicled the double futilities of theology and activism in the twilight years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His sophomore novel was denounced as conservative, polemical and melodramatic by the influential literary theorist, Lionel B. Steiman.

More than to save face among critics and peers, he followed his heart to the fulfillment of his life’s greatest work, merging compassion with creativity towards the fruition of his soul. Although he died before seeing its publication, Rainier Maria Rilke, a fellow Bohemian-Austrian poet and novelist, wrote, as quoted on the back cover of the Compass Books edition, issued in 1967 by Viking Press: “I admire him with all my capacity for appreciating his accomplishment, with the wonderful freedom given to us artists to applaud only when another has reached his utmost goal.”

I took my 51-year-old copy of the book with me back to Turkey, and read it in the spirit of a word often used by desirous literati, voraciously. I ate it up. It’s sadly now in four pieces. With its spine broken, halved, it does not travel well. By coincidence, I recently became friends with two Hatay natives, a film theorist and cook’s assistant. They both invited me to see the land where Werfel became one of the very first to proclaim the plight of the Armenian genocide to Europe. I may go and take my copy of The Forty Days with me, bring it to Moses Mountain and leave it as an offering. Either that, or have the fractured book repaired, the more sensible option as it is a lovely vintage collectible.

Werfel had no such flighty notions when he traveled to the Middle East with Alma and returned in an irrepressible rage. The workers he saw in a Damascene carpet factory were starving, shell-shocked Armenian orphans. In the Spring of 1933, in Breitenstein, a small town in Lower Austria, he marked down a note to open the book he had just finished writing, recounting: “The miserable sight of some maimed and famished-looking refugee, working in a carpet factory, gave me the final impulse to snatch from Hades of all that was, this incomprehensible destiny of the Armenian nation.”

He learned of the genocide there and then, and heard similar stories across Syria and Lebanon, motivating him to research for the grand work of fiction centred on the heroic defense of Musa Dagh, where Turkish troops were defeated, and an exiled mass of Armenian deportees protected under the young Moses Der Kalousdian, the man who became the muse for his protagonist, Gabriel Bagradian, who, though an Armenian by birth, was wholly awash in his Parisian upbringing. The tightrope between two assimilations, European and Ottoman, for such a global minority as the Armenians is drawn in the sand all the more clearly with the characters from Bagradian’s family, Juliette and Stephen, whose travails are ravishing, sensitively written and one might say, considering Werfel’s background, fit for the stage surrounded by a sumptuous cast of characters driven by all of the ecstasies of illicit sex amid epochal violence.

In a March 2018 article in the London Review of Books, seasoned critic Neal Ascherson warned contemporaries of the classic’s syrupy prose, or what he called “gaudy pages of descriptive detail” in the unabridged, original 912-page, 1934 translation by Geoffrey Dunlop, recently revised by James Reidel to full length for its latest rerelease in January by Penguin. With praise for its heralding the oncoming tidal waves of 20th century genocide, Ascherson wrote more sympathetically: “For Armenians, it remains unique and precious: for all its minor inaccuracies, it’s the one work whose urgency and passion keeps the truth of their genocide before the eyes of a world that would prefer to forget about it.”

As a literary accomplishment, Werfel himself likely saw his chapter based on the historic records of a conversation between Enver Pasha and Pastor Johannes Lepsius as the most successful in terms of its grab for the reader, as he chose to highlight it for his 1932 lecture tour of German cities. Truly, its pages are as readable as they are memorable, detailing the stereotypical Orientalist guile of Enver, head of the insurrectionist Young Turks who then stood to govern the embattled, moribund imperial reaches, as he leans hard against the desperate, Western philanthropism of Lepsius, whose appeals are echoed by humanitarians on the front line of international government aid to postwar genocide victims, from Bosnia to Rwanda, Cambodia to Darfur.

What is particularly invigorating about a contemporary reading of The Forty Days is how insightfully and keenly Werfel observes late Ottoman society in its transitional state. He speaks of the teskeré, that loathed interior travel document for officiating identity within the imperial realms, and of how by the second decade of the 20th century, Armenians, Greeks and Syrians were all wearing European dress, only they differed by the hat. Most sensuously, he writes such potent culinary phrases as the “onion-laden reek of mutton fricassees” still popular in the region.

That genocide is tempered by racism is an unsavoury reality honed in the book where Werfel pits the French and Armenian identities against one another. For example, the born-and-raised, ethnic Armenians of the Anatolian east become the epitome of Rousseau’s noble savage when Bagradian’s gentle son, Stephen, whose eventual fate is as hapless war hero and martyr, watches his indigenous, Armenian peers from afar. Towards the middle of the narrative, with the internally displaced refugees astray on the Damlayik plateau, Werfel writes:

They were interwoven with the very nature in which they lived. Their hills were as much a part of them as their flesh, so that to differentiate between outward and inward became impossible. Every leaf that stirred, every fruit that dropped, the rustling of a lizard, the faint splash of a far-off waterfall -- these myriad stirrings had ceased to be mirrored by thei senses; they formed the very heart of those senses themselves, as though each child were himself a little Musa Dagh, creating it all within his own body. (346)****

And of Juliette, the unfaithful wife of the equally adulterous Bagradian, the Austrian-Bohemian author digs into the vein of French identity, with the following lines:

Being French, she had a certain natural rigidity...the French as a rule hate nothing so much as to leave their country, get out of their skin. Juliette shared in a high degree this set quality of her race. She lacked that power of intuitive sympathy which usually goes with formless uncertainties...For fifteen years she had really only been aware that she had married an Ottoman subject. What it really means to be Armenian, the duties and destiny it entails, she had had to discover a few weeks previously, with appalling suddenness. (359)****

Ascherson affirmed, writing for the London Review of Books, that Bagradian and Juliette are, in certain ways, modelled after Werfel and Mahler, who had a stormy marriage, with her being significantly his senior and previously married to Gustav, the genius of national renown. The story’s core human drama also reflects the tendencies to Jewish solidarity that Werfel advanced in his fervent work that stole him from Mahler’s side, leaving her to reconcile the fact that she had not only married a Jew by birth, despite his nominal renouncement, but that she was wedded to a portion of the entire psychological, historical burden that comes with even the most secular of Jewish identities in all of its forms, many of which manifest through personality, art and empathy.

And lastly, Werfel expresses his unequivocal admonishment on the subject of genocide through a wise and beneficent character, the Muslim sage Agha Rifaat Bereket who is the first to warn Bagradian of the atrocities, and eventually returns to Musa Dagh from Istanbul after pleading for innocent lives with gifts of subsistence to the survivors in the midst of the siege, many of them women and children on the verge of death. As the demonic impulse to genocide captivated Werfel’s own countrymen, he wrote with an uncanny, intuitive premonition enough to chill the bones of readers for all time. To end with Werfel’s immortal words:

The most horrible thing that had been done was, not that a whole people had been exterminated, but that a whole people, God’s children, had been dehumanised. The sword of Enver, striking these Armenians, had struck Allah...This, then, is God-murder, the sin which, to the end of time, is never forgiven.

To the old man, it felt as though he were walking through clouds of ashes, the thick death-cloud of the whole burnt-up Armenian race rising between time and eternity. (672-3)****

References

* Tim Arango. “‘Sherlock Holmes of Armenian Genocide’ Uncovers Lost Evidence”. The New York Times. April 22, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/22/world/europe/armenian-genocide-turkey.html

** Neil Ascherson. “Howitzers on the Hill”. London Review of Books. Vol. 40 No. 5. 8 March 2018. https://www.lrb.co.uk/v40/n05/neal-ascherson/howitzers-on-the-hill

*** “MGM was to produce a film version of The Forty Days of Musa Dagh in the 1930s.” The 100 Years 100 Facts Project. Accessed August 10, 2018. http://100years100facts.com/facts/mgm-produce-film-version-forty-days-musa-dagh-1930s/

**** Franz Werfel. The Forty Days of Musa Dagh. Translated from the German by Geoffrey Dunlop. Viking Press. New York. 1967.

*

Matt Hanson is a writer and journalist living in Istanbul, and New York, where he works as an arts and culture reporter for various internationally-distributed newspapers and magazines. His piece, “Modern Romaniote Odyssey” was excerpted to introduce his forthcoming photobook, The Clouds of Ioannina, featuring oral histories with one of Europe’s oldest and vanishing minority communities. He is currently producing an anthology of Romaniote Literature to forward an English readers’ appreciation for the Greek-speaking Jewish literary contribution from antiquity through the medieval era to the contemporary.

*

You can find The Forty Days of Musa Dagh here.

*

Next: