You’re Ironing My Head: Shared Western Armenian and Turkish Idioms

by Jennifer Manoukian

Learning Turkish is filled with moments of déjà-vu for Western Armenian speakers. The words we once heard in our childhood kitchens and living rooms—but never in our classrooms—we now see written on whiteboards and enshrined in textbooks. The familiar lilt of conversations that once permeated our family gatherings we now hear captured in comprehension exercises. And the Armenian grammar that once seemed too convoluted to master now comes to our rescue as we struggle to decode serpentine Turkish sentences.

While Armenian and Turkish belong to distinct language families, their similarities today should come as no surprise. Western Armenian—the language spoken by Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and their descendants around the world—rubbed shoulders with Turkish for more than four centuries. This enduring contact had varying effects on Armenians in the empire. Some shifted fully to Turkish, speaking it as their mother tongue; others adopted diglossic bilingualism, using Turkish in certain realms of life and Armenian in others; and others still spoke a variety of Western Armenian that was peppered with Turkish loan words and calques (i.e., literal translations). It is this third outcome that survived the fall of the Ottoman Empire and persists—often unbeknownst to Armenians themselves—in Western Armenian today.

As other examples of language contact show, language change within imperial contexts is often largely unidirectional with the language of the conquered changing more radically than the language of the conqueror. This pattern also holds for Turkish and Western Armenian. Beyond words that hint at shared origins (e.g., թոռ [tor] & torun; էշ [esh] & eşek) and the great many direct borrowings from Turkish (e.g., արապա [araba] & araba; պօշ [bosh] & boş; իշտէ [ishdé] & işte), calques—or literal translations—from Turkish abound in both colloquial and standard Western Armenian. At times these instances are obvious to the naked eye (e.g., վազ անցնիլ [vaz antsnil] & vaz geçmek; թաք թուք [tak touk] & tek tük), while others can only be detected by those with a knowledge of the structure of both languages (e.g. նորէն [noren] & yeniden; մնաք բարով [mnak parov] & hoşçakalın; ողջ ըլլաս [voghch ëllas] & sağ ol).

Forms of reduplication can also be seen in the colloquial forms of both languages: echo reduplication (e.g. գիրք միրք [kirk mirk] & kitap mitap), emphatic reduplication (e.g. կաս կարմիր [gas garmir] & kıpkırmızı) and doubling (կամաց-կամաց [gamats-gamats] & yavaş yavaş) all bring smiles to the faces of Armenian students of Turkish and Turkish students of Armenian.

Despite the near inevitability of language change in a case of such long-term contact, the imprint of Turkish on Western Armenian is rarely discussed in Armenian circles and is essentially unknown to Turkish speakers. This reticence on the part of Armenians to acknowledge the lingering traces of their Ottoman past are tied, I have argued elsewhere, to the politics of Armenian Genocide recognition and the comfort many Armenians still take in nurturing prejudice against a people they are set on branding enemies to the exclusion of all else.

***

In 1962, the celebrated Egyptian Armenian cartoonist Alexander Saroukhan (1898-1977)— known across the Arab World for his political cartoons—published a collection of sketches entitled Տե՛ս խօսքերդ (Look at What You’re Saying!). In this collection, he drew literal depictions of commonly used Western Armenian turns of phrase. Beginning as a way to pass the time at school in early-twentieth-century Constantinople, Saroukhan began publishing his linguistically inspired cartoons in the satirical Armenian newspapers Կավռօշ (Gavroche) in 1921-2 in Constantinople and in Հայկական սինեմա (Armenian Cinema), which he founded in Cairo in 1925.

What Saroukhan does not mention is that many of his idioms also exist—often word-for-word—in Turkish. Below is a sampling of cartoons from Տե՛ս խօսքերդ comprised of expressions still used today in both Western Armenian and Turkish. Saroukhan writes that when he first began publishing these cartoons, they awoke an unexpected kind of curiosity about language in his Armenian readers. My hope is that this (re)introduction of Saroukhan’s work will stir a similar sense of curiosity—this time in the minds of two peoples. Saroukhan’s sketches have the power to lead Armenian speakers to see the undeniable vestiges of their Ottoman past embedded in their daily language and to lead Turkish speakers to grasp the life their language continues to live among Armenians today.

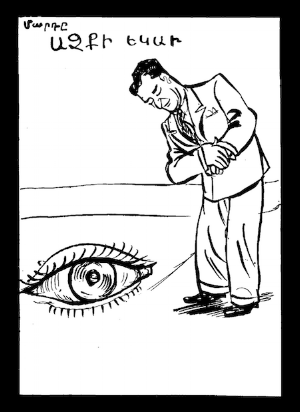

1. Literal: I passed the newspaper through [my] eye.

Figurative: I took a look at the newspaper.

1. Թերթը աչքէ անցուցի։

Gazeteyi gözden geçirdim.

2. Literal: I threw an eye onto the newspaper.

Figurative: I glanced at the newspaper.

2. Աչք մը նետեցի թերթին վրայ։

Gazeteye göz attım.

3. Literal: The girl bit my eye. (Armenian)

My eye bit the girl. (Turkish)

Figurative: The girl caught my eye.

3. Աղջիկը աչքս խածաւ։

Gözüm kızı ısırdı.

4. Literal: The man’s eye stayed behind.

Figurative: The man left something undone.

4. Մարդուն աչքը ետին մնաց։

Adamın gözü arkada kaldı.

5. Literal: The man came to eye.

Figurative: The man was affected by the evil eye.

5. Մարդը աչքի եկաւ։

Adam göze geldi.

6. Literal: My wife has been eating my head for days. (Armenian)

My wife has been eating the meat of my head for days. (Turkish)

Figurative: My wife has been nagging me for days.

6. Քանի օր է կինս գլուխս կ՚ուտէ։

Günlerden beri hanımım başımın etini yiyor.

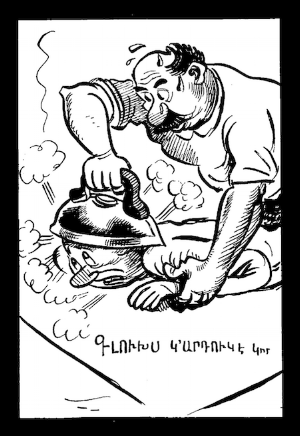

7. Literal: He is ironing my head.

Figurative: He is badgering me.

7. Գլուխս կ՚արդուկէ կոր։

Kafamı ütülüyor.

8. Literal: I joined [his] nose and mouth.

Figurative: I beat him up.

8. Քիթ բերանը մէկ ըրի։

Ağzı burnu birbirine karıştı.

9. Literal: She invited [us] with half a mouth.

Figurative: She invited [us] half-heartedly.

9. Կէս բերան հրաւիրեց։

Yarım ağız davet etti.

10. Literal: The man is looking for a mouth.

Figurative: The man is trying to extract information.

10. Մարդը բերան կը փնտռէ կոր։

Adam ağız arıyor.

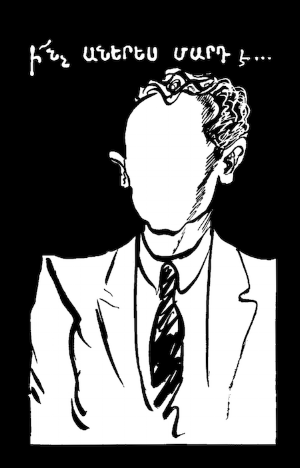

11. Literal: What a faceless man he is.

What a sourpuss he is. (Turkish)

Figurative: What a shameless man he is. (Armenian)

11. Ի՜նչ աներես մարդ է։

Ne suratsız* bir adam.

*Suratsız is also used in colloquial Western Armenian to mean sourpuss.

12. Literal: Should I give [you] the five brothers?

Figurative: Should I slap [you]?

12. Հինգ ախբարիկ տա՞մ։

Beş kardeş vereyim mi?

13. Literal: The woman’s body became thorns thorns. (Armenian)

The women’s hairs became thorns thorns. (Turkish)

Figurative: The woman got goosebumps all over.

13. Կնոջ մարմինը փուշ փուշ եղաւ։

Kadının tüyleri diken diken olmuş.

Permission to use Saroukhan’s sketches is courtesy of his granddaughter Sylva Neredian Pladian.

Thank you to Maral Aktokmakyan, Hagop Gulludjian, Beyza Lorenz, Daniel Ohanian and Asbed Vassilian for their help with this piece.

*

Jennifer Manoukian is a doctoral student in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research focuses on the language practices of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.