Review: & Silk & Love & Flame, Birhan Keskin

By Erica Eller

Every culture has a poetics of pathos.

In Greek, pathos means “suffering.” Aristotle defined pathos as one of the rhetorical modes of persuasion. It involves eliciting emotion to produce a desired effect on one’s audience (1).

In America, we have the blues, with its origins in the spirituals sung by African American slaves on plantations. The blues are laden with feelings of sorrow and hardship. However, they evolved to encompass personal themes, and political messages, without loosing their roots in suffering. The lyrics by Irving Mills of Duke Ellington’s Mood Indigo take us to that poignant state (especially when sung by Billy Holiday):

'Cause there's nobody who cares about me

I'm just a soul who's bluer than blue can be

When I get that mood indigo

I could lay me down and die. (2)

A feeling of deep misery is wedded to the potency of the blues, which has been disseminated and adopted by cultural art forms of all kinds in America and beyond.

In Spain, poet Federico Garcia Lorca identified duende as the tragic streak of madness found in the work of great flamenco dancers and bull fighters. He describes it as the “earth spirit of irrationality and death,” in his book of poetic criticism titled In Search of Duende (3). This form of pathos found in Spanish poetics emphasizes dark and mysterious undertones of creative impulses.

For Turkish poet Birhan Keskin, a famous line of the seventeenth century folk poet Karacaoğlan concretizes the theme of pathos: “Bir Ayrılık, bir yoksulluk, bir ölüm” (A separation, a destitution, a death). In a shared “Şiir Masası” (“Poetry Roundtable”) interview conducted by Deniz Durkuan with Birhan Keskin, Ezel Akay, Serenad Bagcan and Hakan Gercek published in Pul Biber (4), Keskin points out that these are three primary concerns in Turkish poetics, with the themes themselves originating four or five thousand years ago with the Sumerians.

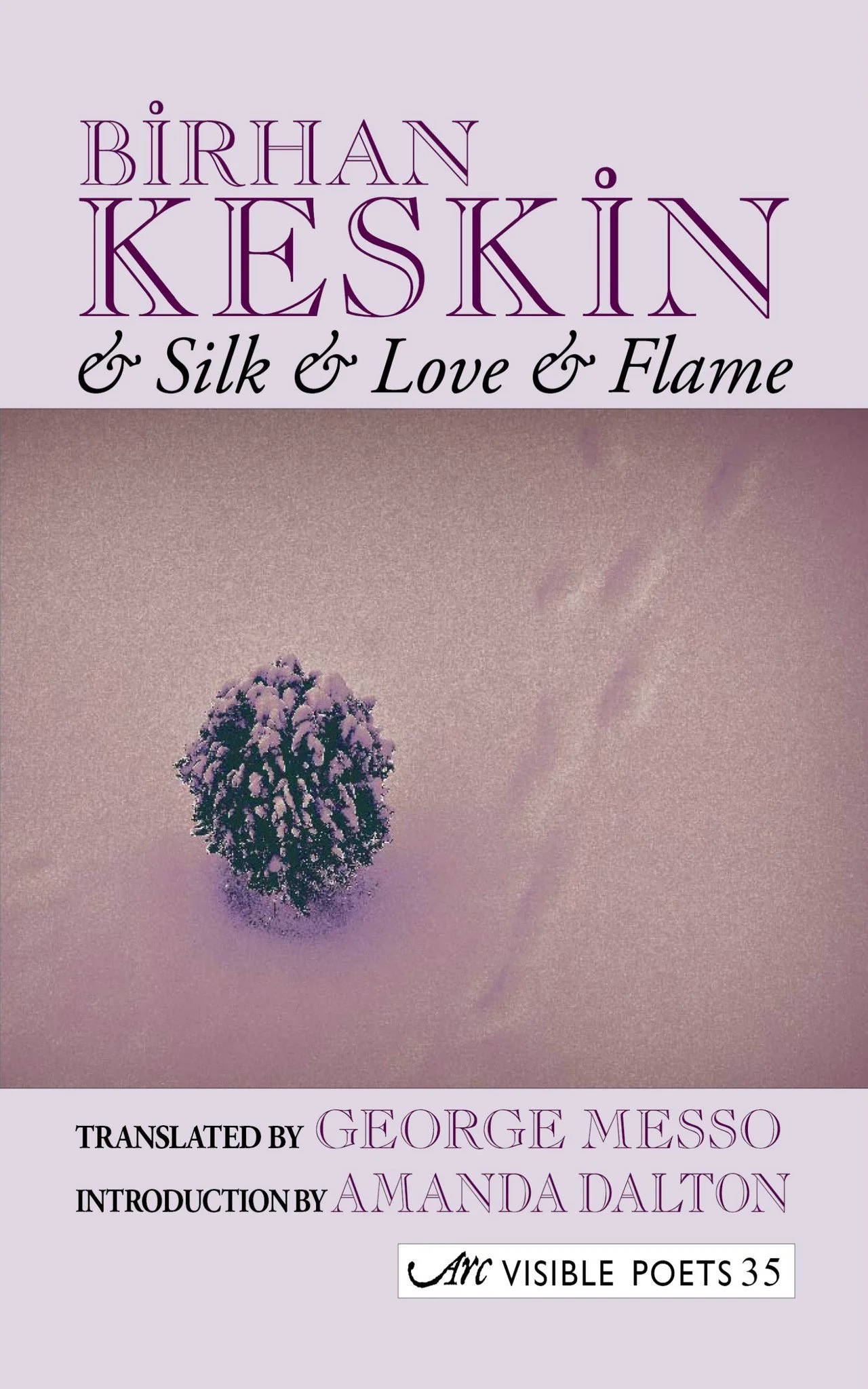

& Silk & Love & Flame is the first and only book-length translation of Birhan Keskin’s poems into English. Translated by George Messo, the collection includes poems from Ba (2005), Yeryüzü Halleri (States of the Earth) (2002), 20 Lak Tablet (20 Polished Tablets) (1999), Cinayet Kışı (Winter of Murder) (1996), Bakarsın Üzgün Dönerim (I May Return Unhappily) (1994) and Delilirikler (Crazy Lyrics) (1991) (5). A female bard in a land dominated by male poets, Keskin was only the second woman to win Turkey's prestigious Golden Orange Award for her collection of poetry, Ba, in 2006.

Messo adoringly writes in his introduction, “Fluid and lucid, Birhan's poems inhabit a space between cognition and remembering, testimony and invention. For the translator, these are qualities that can appear like a mirage, with such tantalizing clarity, only to disappear the moment we try to speak the work in English”(6). He casts her work in light of her importance as a city-dwelling naturalist of introspection. I would agree and add that her work uses personal intimacy and nature to enact the universally tragic themes of separation, destitution and death. It also renews these themes by granting these pillars feminine significance.

She casts the winter season, traditionally understood as symbolic as the turn towards old age and death, as a process of containment in the first poem of the collection, “Hüzzam (Melody)”:

You turned me into dry grass

That sweats out its juice

Before I turned forty, why?

Now my breath is mist on glass in the winter room

Once it was purple wind on the steppe.

Interestingly, I could not help but read feminine significance in the enclosure it describes, as the women's sphere has traditionally (and stiflingly) been associated with domestic, indoor spaces. The poem describes the results of a process, arriving in the aftermath of some unnamed force of change: a love followed by a separation. The seasons are alluded to, as the speaker finds herself in an indoor space, a “winter room,” though her breath was once unfettered “purple wind on the steppe.” Messo translates “eflatun” as “purple”, a choice I disagree with, because the using the more literal “lilac” or “lavender” would have left us with much stronger sensory impressions; these flowers originate in nature, connoting a scent and season: spring. Indeed, the seasons have changed in the poem, and as a result, the speaker has lost vitality, youth and even freedom. The age of forty also suggests an important turning point in a woman’s life, as it is near to the time when she is no longer fertile. “Why?” she asks, as if some arbitrary abuse remains unsettled.

In another poem, “Incir (Fig),” a fruit lies on the ground, in a state of amnesia:

Remembers neither leaves nor sun

Nor falling from its branch

Its honey like a dried desire within

Still in its place from last autumn

Fertility has faded, the fruit has fallen, the moisture dries up and all of this occurs in the aftermath of love—a period of loss. The natural imagery helps elucidate a familiar process of loss and forgetting through metaphor. In a sense, Keskin allows us to understand the metaphysics of menopause in this poem and others in the collection Ba (5). She even creates a neologism that comprises this condition as one of the headings to the subsections featuring this poem in Ba: “Monopoz.” While this detail is lost in the translated collection, it helps contextualize her poem. The admixture of monotony and menopause offers a somewhat apt description of modernity, as if the world has become an aging woman. The other headings in Ba include “Monogam” and “Monolog.” These words offer a clever word-chain through the repetition of the prefix “mono” taking our minds to different suggestive zones (monopoz/menopause/loss of fertility, monogam/monogamy/faithfulness, and monolog/monologue/speech). Indeed, we can understand the shifts embodied in her poems viscerally on the plain of individual experience, as well as historically, as if we are living through society’s own menopause. Obviously, in our time of rapid industrialisation, our lives as urban dwellers pass between walls more so than out in open spaces.

Though also absent from the collected works in English, Ba starts with a dedication and epigraph that reveals Keskin’s affinity for wordplay. Her dedication reads: “Dilimde yarım bir hece gibi kalan babamın güzel hatırası için ...” (“There’s half of a syllable that stays on my tongue as a reminder of the fine memory of my father ... ”) (7). Naturally, our mind shifts to the title of the collection Ba, which is half of the word “Baba” (papa or father). She then compounds the associations of the syllable Ba with her epigraph. It is a couplet of Yunus Emre’s which reads, “Cümle alem gizlidir bir elifte / Ba dedirtmen bana sonra azarım.” (“There’s a whole world hidden in an Elif / If you make me say Ba I’ll go crazy”) (8). Here, Yunus Emre refers to the first two letters of the Arabic alphabet and the second letter, 'Ba,' becomes a point of delirious saturation of linguistic possibility. Just the first pages of the book invoke this complex series of associations: eliding the second Ba of Baba, and preceding the Ba with Elif. This clever wordplay can be found throughout Keskin’s original works, but unfortunately it remains less palpable in translation.

Keskin’s brevity is such that a poem will reveal a scene or landscape compressed into a few lines that leave the reader perplexed. Take, for instance, the poem from & Silk & Love & Flame, “Vaziyet (State of Affair)”:

I stand in the oleaster’s silver side

A side of me long darkened

When seen from afar:

Two chimneys as if blocked with soot

If they reach out to each other, flame no longer touches

On the one hand, we are provided the image of an oleaster tree with its long, silvery leaves. On the other hand, we may envision a person standing alongside her shadow on the trunk of the tree, or a person standing beside a ghost, or another tree standing beside the oleaster, perhaps a tall, dark cypress. A shift in perspective is used to introduce a second set of images. From a distance, we sense a feeling of separation, in which the “flame” is no longer shared. Again, we sense some aftermath of warmth and love. The difficult part is connecting the near and far views introduced by the poem. The play of light and shadow emphasizes the loss, where the absence of light is likened to soot, the residue of some past flame. Without accessing a definitive relationship between the parts, we sense clearly an insurmountable rift of separation.

Notably, the natural imagery in the poem doesn’t lead us to any connotative conclusions. As Amanda Dalton writes in her introduction to the collection & Silk & Love & Flame, “This is not pastoral writing, but a fiercely personal writing, writing of the self, that consistently transmutes into something strange, experimental and bold in its use of elemental imagery” (9). One of the ways Keskin manages such perplexing lines is through specific gaps in meaning that arise out of non-recoverable deletions, a quality that marks the difference between prose and poetry for critic Samuel Levin (10). Such deletions are also a significant feature of compression, another quality that marks poetic verse.

Keskin’s compressed imaginary landscapes offer poetic snapshots, like the Turkish miniature paintings we can find in museums. Orhan Pamuk's My Name is Red offers a fictional account of the lives of miniaturist painters in the sixteenth century. Pamuk brings up an important question of representation in the chapter “I am a tree,” when a tree drawn on a page that has lost its surrounding book speaks to us. The painted tree describes how it has been separated from its book, but it cannot remember how the separation has happened. As a tree represented by eastern aesthetic values, rather than francophone realism, the tree explains his preference for eastern representation: “I didn't want to be a tree. I wanted to be its meaning” (11). Likewise, Birhan Keskin's poems offer a similar effect; her brief, shareable poems never blind us through the optics of realism.

The simultaneous simplicity and elusiveness of Keskin’s poems seems at once modern and ancient, as compression is not only a hallmark of contemporary poetry, but also a prominent feature of ancient Turkish poetics. As Charles F. Horne writes in The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East, “We are told that when the first Turkish epic poet Ahmedi presented to Sultan Bajazet's son his long epic history of Alexander the Great, the prince rebuked the poet's years of labor, saying that one tiny, perfectly polished poem would have been worth more than all the epics. Hence, it is chiefly to the polishing of tiny poems that the poetic genius of the Turks has been applied” (12).

A favorite example of such brevity for readers and critics alike is Keskin’s “Balık (Fish)”:

Once I fell for the lure

Ah my wounded tongue

I cannot speak

The image of the fish caught on a lure and the metaphor of a hurt lover seamlessly collide. The emphasis on speech (or the loss of it) likewise reveals Keskin’s continued emphasis on the construct of language, as if to remind people of her medium.

Finally, the elusive quality of Keskin’s poems should be explored a bit further. She states that Turkish is very associative (“Türkçe çok çağrışımlı”) and she also points out that with so much compression (in the Turkish language) you can open up a universe (“Bu kadar kıt sözcükle bu kadar geniş bir evren yaratıyoruz”) (13). Indeed, the agglutinative suffix-ending grammatical structure of Turkish lends itself to elliptical constructions. Much in the language can also be telegraphed through a rich range of idioms familiar to any native Turkish speaker. Unfortunately, for many non-Turkish speakers, much is lost in translation. However, the translations offered by Messo give enough of a sense of the elemental nature the poems, providing rich connotative textures in English as well.

Oftentimes Keskin’s poetic effects depend on a loosening of reason’s hold on our understanding. She asserts that a lucid dreamlike-state is an essential quality of the poetic art form: “Aslında bütün sanatlar ama özellikle de şiir rasyonelle irrasyonelin arasında bir noktada yer alır” (“Actually all art, but especially poetry takes place at a point somewhere between rationality and irrationality”) (14). In his book, Why Poetry, Matthew Zapruder explains this in-between state, which is inherent to good poetry, as follows: “Somewhere between not knowing and full knowledge there is an intermediate, contradictory state of half knowledge (what we would also call reverie, drifting, or lucid dreaming), where one goes in order to write poetry, and when one reads it” (15). Borrowing the phrase half-knowledge from Keats, Zapruder suggests that poetry honors a different sort of truth than “categorical conviction.” Transformative, associative and moving, good poetry reawakens us to an intuited form of knowing that underlies language.

Perhaps it is too much of a clichéd binary, but the East/West dichotomy implies a relevant cultural binary when thinking about Keskin’s threshold of rationality. Whereas the West is known for rationality, the East has been lauded for its mysticism. Keskin’s work falls between these pillars geographically and stylistically. Her uncanny emotive clarity and musical resonance offers an authentically Turkish mode of expression. I’m not the first to suggest this, either. Many admirers have described Birhan Keskin as the era’s most authentic poetic voice.

From another perspective, the need for poetic ambivalence often arises during historical periods when artists feel under siege. In their paper on the translation of Keskin’s poems in & Silk & Love & Flame titled “English Translations of Birhan Keskin:

A Metaphor-Based Approach to Poetry Translation,” Göksenin Abdal and Büşra Yaman write that following the paradigm change in the 1980s, “themes from the nature and references to natural elements gradually start to take their place in the works written by the poets in those years. Owing to the political pressure and societal changes after the military coup in 1980, the poets generally tend to refrain from using clear-cut statements criticizing the political agenda in the country, and rather choose to use a language comprised of implicit and metaphorical expressions” (16). While Keskin’s work can be read in terms of universal themes, it can also imply another kind of contemporary political pathos across the span of years her books of poetry were conceived. To give an example, her most recent collection of poems, Fakir Kene (Impoverished Tick), deals with violence towards women both explicitly and implicitly. One of the poem’s titles itself is the URL of a website (http://www.anitsayac.com), which has been set up to count and name women who have died in Turkey due to violence (17).

And what of these feminine undertones? I don’t get the impression that Keskin’s poetry comprises a politics of self, à la Adrienne Rich, who is known for fusing the personal and the political. Instead, she writes with an aspiration to merge the personal and the universal. Her separation (bir ayrılık) is a feminine loss of love, her destitution (bir yoksulluk) is a feminine loss of fertility, creativity and abundance, and the death (bir ölüm) in her work is reflected through her embodied female lens. Reading her poems, we find feminine suffering with universal implications. While most of the poems in the collection & Silk & Love & Flame appear to have been selected for their expressive intimacy, the poetry is ripe with that rhetorically poignant pathos which explodes the personal, veering towards a universal resonance.

Birhan Keskin’s poetry transmutes our modern sorrows, while it also reinvigorates a centuries’ old Turkish poetic tradition. Keskin offers compelling original insights that derive from her depth of feeling and mastery of the possibilities the Turkish language provides. I urge you to explore her poetry by reading & Silk & Love & Flame.

Notes:

(1) Aristotle. Rhetoric. Trans. W. Rhys Roberts. New York : Modern Library, 1954.

(2) Ellington, Duke and B. E. Bigard. Mood Indigo. Lyrics by Irving Mills. Victor Records: 1930.

(3) Lorca, Federico Garcia. In Search of Duende. Ed. and Trans. by Edward Maurer, et al. New York: New Directions, 2010.

(4) Keskin, Birhan, Ezel Akay, Serenad Bagcan, and Hakan Gercek. “Şiir Masası,” Ed. by Deniz Durkuan, Pul Biber, March 2016.

(5) George Messo, Translator’s Preface. & Silk & Love & Flame by Birhan Keskin. Arc Books, 2010.

(6) Keskin, Birhan, Ba, Istanbul: Metis Kitap, 2005.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Ibid.

(9) Amanda Dalton, Introduction. & Silk & Love & Flame by Birhan Keskin. Arc Books, 2010.

(10) Samuel Levin, “The Analysis of Compression in Poetry,” Foundations of Language, 7 (1971), 39.

(11) Pamuk, Orhan. My Name is Red. Trans. Maureen Freely. New York: Penguin Random House, 2010.

(12) The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East. Ed. Charles F Horne. New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pp. 259-325, 1917.

(13) Keskin, Birhan, Ezel Akay, Serenad Bagcan, and Hakan Gercek. “Şiir Masası,” Ed. by Deniz Durkuan, Pul Biber, March 2016.

(14) Ibid.

(15) Zapruder, Matthew. Why Poetry. New York: Harper Collins, 2017.

(16) Abdal, Göksenin and Büşra Yaman. “English Translations of Birhan Keskin:

A Metaphor-Based Approach to Poetry Translation,” in Litera: Journal of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Vol. 27, Issue 2, 2017, pp. 45-63.

(17) Keskin, Birhan. Fakir Kene, Istanbul: Metis Kitap, 2016.

*

Erica Eller is a writer and editor from the United States, living in Istanbul. She's lived in Istanbul so long that she now fuels her writing with çay instead of coffee.