The Man who Loved Emily Dickinson from Afar

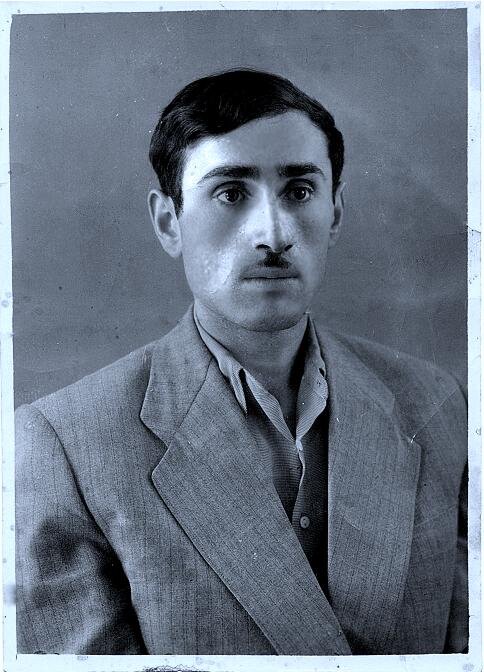

Mikheil Nishnianidze

Giorgi Nishnianidze

Mikheil Nishnianidze offers this introduction to his memoir of his father: “The following piece is a memoir about a Soviet Georgian translator who fell in love with Emily Dickinson’s poetry. Giorgi Nishnianidze’s poetic and literary translation legacy leaves us with a few hundreds of pieces by several dozen Anglophone poets and writers. The regime reluctantly accepted western creative work, forcing it through the prism of Marxist ideology, despite never encouraging independent artistic expression in minority languages. An eye-witness account by the son of the translator, the essay offers a retrospective analysis of the 70 years of the USSR. The author speculates about the artistic freedom and the agility required from Soviet artists who tried to circumvent strict communist censorship.”

I first heard of Emily Dickinson from my father, Giorgi Nishnianidze, a well-known translator of English poetry and prose into Georgian during the last thirty years of the Soviet Union. By the time he discovered her poetry he was already famous for his translations of Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare, Lord Byron, Oscar Wilde, William Wordsworth, Walt Whitman, T. S. Eliot, Jack London and many others. His works earned him the renowned translation award – the Ivane Machabeli Prize – offered by the Union of Writers of the Soviet Republic of Georgia.

Father was born in 1935 in Tbilisi, the capital of the Republic of Georgia, only two years before the outbreak of the Great Purge of 1936 to 1938, which shocked the USSR and its weather-beaten population – who could hardly have felt they could be surprised by anything after the massacres of the Revolution. Stalin and his team had no mercy for any opposition. Intolerance became contagious, and it didn’t take long for it to become the social norm. By the time all dissenters had been dealt with, the crowd outlawed new enemies, often for any arbitrary denominator, any noticeable social category – physicians, military figures, academics, teachers.

Since my grandfather was a Cavalry Captain, his family would most likely have fallen during these persecutions, but they were saved by a chance misfortune, when he died from cancer at 29, just before the Great Purge began. My father was only three months old at the time. My grandfather’s brother was less fortunate. A Lieutenant Colonel in the Corps of Engineers, he was later executed. My great-aunt was exiled to Siberia, a fate typical for hundreds of thousands of families at the time. The apocalyptic scale of persecutions dwarfed the entire population.

სიკვდილ-სიცოცხლეს - ამ ძველ გიგანტებს -

სძინავთ და მათი არ ისმის ჩქამიც,

წვრილფეხობას კი - სარეკელას თუ

ფარვანას, ალმა რომ შთანთქა ლამის -

სწამთ, ბრმა შემთხვევა წარმართავს საგნებს

და ყველაფერი მთავრდება ამით

LIFE, and Death, and Giants

Such as these, are still.

Minor apparatus, hopper of the mill,

Beetle at the candle,

Or a fife’s small fame,

Maintain by accident

That they proclaim.

Instead of “accident” in the original, Giorgi Nishnianidze replaced “A fife’s small fame” with the more emphatic “Blind Chance that manages matters and is the end to Everything,” making it more fatalistic.

Living a “small life” (Fr307), discreetly, helped the family escape the existential clash of cultures. My bebia (ბებია) (grandmother in Georgian), a country woman with three orphaned sons, made her living by sewing, thus slipping under the radar, representing no threat to anyone.

Father was a frail child. He refused to walk even at the age of twelve months. So his family took him to a freshly made grave and made him walk over it, a Georgian practice based on old beliefs. The magic worked and he grew into a very independent boy, perhaps partly because of the lack of parental control from my overworked bebia, desperately trying to make ends meet. She was almost illiterate, yet she loved singing as she worked, a habit she maintained all her life.

Total control

Stalin was a controversial figure. He was a strong leader who knew how to manipulate people. He had a good theological education and used his expertise to create an ideology comparable to a religious cult. At the same time, however, he was a weak manager who failed to bring the country’s struggling economy together. His contradictory persona becomes most obscure in relation to the arts. Stalin shared Lenin’s instinct for “weaponizing” the arts; but he was a mediocre consumer, resentful of anything exceeding the ordinary or mundane.

Life was hard in Stalin’s Tbilisi, especially during war-time. The authorities distributed bread, vegetable oil, kerosene and rationing tickets for some other essentials. But this was barely enough to survive, and indeed many people died from malnutrition. In winter, everybody would gather in one of the neighbors’ homes to socialize and save firewood. The most popular topic was food; they tried to remember different meals they used to have before the war. In spring the first greenery made their ration more diverse. In summer a main entertainment was swimming in the deep and treacherous Mtkvari River that flows through the city. School was not the first priority for children. The city streets maintained their own criminal hierarchy. Father didn’t choose a life of street crime, but he wasn’t a diligent learner, and even had to repeat a grade. All of sudden in his mid-teens he became obsessed with reading fiction, not only in Georgian but in Russian and English too.

The game changer

The fight against the Nazis brought moral satisfaction and a sense of justification to the Soviet people. It loosened the grip of the State because all attention was turned to the struggle. The hard-bitten war generation brought forth outstanding personalities in different areas of human creativity.

Isaiah Berlin commented on the period that: “There is an uncommon rise in popularity with the soldiers at the fighting fronts for the least political and most purely personal lyrical verse by Pasternak . . . Akhmatova, and Blok, Bely, and even Bryusov, Sologub, Tsvetaeva, and Mayakovsky. . . . Distinguished but hitherto somewhat suspect and lonely writers, especially Pasternak and Akhmatova, began to receive a flood of letters from the front quoting their published and unpublished works . . .”

My two elder uncles also started writing poetry at almost the same time as my father. One of them, the eldest brother Shota, later became a famous Georgian poet; the middle child, Otar, became a dental technician and soon quit writing poetry. Nevertheless, he was an interesting character, a Bohemian hedonistic drinker with an anarchistic outlook who loved to recite his favorite poets when he was drunk.

ჩვენ ჯერ არ ვიცით, რა მაღლები ვართ,

ვიდრე არ გვეტყვის ვიღაც: ადექით!

მაშინ ხომ - გეგმა თუკი არ ტყუის -

ავისვეტებით ღვთის სიმაღლემდე -

არად იქცევა თვით ჰეროიზმიც,

რაზედაც ქვეყნის პოეტნი ჰყეფენ,

მაგრამ წყრთებს ჩვენვე ვიკლებთ გზადაგზა

იმის შიშით, რომ არ ვიქცეთ მეფედ.

We never know how high we are

Till we are called to rise;

And then, if we are true to plan,

Our statures touch the skies—

The Heroism we recite

Would be a daily thing,

Did not ourselves the Cubits warp

For fear to be a King—

This translation by Giorgi Nishnianidze is almost an exact copy of the original, except for one phrase that he translated as: “Annihilated (is) even the Heroism that poets of the world are barking about,” which sounds much more caustic than Dickinson’s phrase.

Eventually, father’s self-taught learnings allowed him to pass the necessary exams and enroll at Tbilisi State University’s Department of Western European Languages, specializing in English. He graduated from the University and was dispatched to a village school to teach English, where he met his future wife, Valentina Borodavko, a teacher of Russian. Being a school teacher was a low-paying job with dubious potential for promotion, so he had few choices for the future. One career for a foreign language-speaking male was that of an intelligence officer. A few years later he was approached by the state security service with an offer he could hardly refuse. However, to his satisfaction, he was finally considered unfit for service because of his poor eyesight. Otherwise, his recruiter later confided, he would have ended up in Afghanistan.

He left the village school and tried several positions, teaching classes at Tbilisi State University, working as an education coordinator, as a manuscript reader for a literary magazine, and even tutoring. He didn’t abandon his literary pursuits, although they couldn’t provide a decent living for his small family. His first remarkable poetic success was the translation of The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, which made him famous in artistic circles.

Khrushchev’s Thaw and Brezhnev’s Time

Soviet soldiers had seen Europe during World War II, and people in the USSR had learned there was a different life elsewhere in the world. They began to pose questions that official ideology could not answer. It was impossible to justify using former violent measures now, against the Heroic Soviet People. Direct control was replaced by a hidden kind. It was a time of more carrots and fewer sticks. But spiritual starvation stripped the people of enthusiasm and the ordeals of torment and torture were replaced by an era of stagnation. Their common sense so long abused by brainwashing, people stopped believing anything. The arts followed reality: after being fed up with vulgar Soviet realism, Georgian artists turned to grotesque forms, bizarre narratives and exaggerated perceptions of self-identity and their culture. In the 1970- 80s the pandemic of caution prevented people from sharing their inner world.

Literary translations became my father’s own way of escaping sordid reality and eventually his endeavors gained him recognition. After many years of small part-time jobs he was offered an editor’s position at the newly established Chief Editorial Collegium of Literary Translations and Literary Relations and was soon promoted to the position of Managing Editor and Deputy Director. This agency, with its peculiar name, was in charge of all literary translations in the Soviet Republic of Georgia. The staff enjoyed decent salaries and a certain editorial liberty, and though the list of foreign authors eligible for translation was restricted by censorship, the liberal environment and direct relations with foreign counterparts, including those from western countries, boosted creativity and produced dozens of excellent translated works that broadened viewpoints and enriched the language. There was also a school for literary novices. It’s hard to tell who came up with this experimental idea but it was definitely backed by someone in the top leadership of the Soviet Republic of Georgia. Perhaps the main purpose was to gather all liberal thinkers and creative people together, i.e. potential troublemakers, which would make it easier for the authorities to control them – if not by the stick then by the carrot.

For the first time my father had a stable, contented life with a regularly paid salary while doing things he loved: teaching young people, working on translations, and associating with like-minded people of the same pursuits. His new status also protected him from the authorities. He had never enjoyed stability before because of family difficulties and his nonconformist personal positions. However, the relative stability and contentment in his new situation ironically exposed the existential anguish formerly masked by his efforts to eke out a living.

Around this time, Father discovered Emily Dickinson’s poetry, and she became his favorite poet. The encounter was quite accidental. Dickinson’s austere style matched the desolation of Soviet life; her numerous cognitive revelations where words lose substance, and then couple to express a meaning beyond the ordinary, allowed her to express forbidden ideas. In his translations of Emily Dickinson, Giorgi Nishnianidze conveyed his own comparable experiences.

მთლიანად მხოლოდ ორჯერ გავკოტრდი,

ორჯერვე ისიც შავი სამარის

წიაღ და ორჯერ მათხოვარივით

ვიდექ ღვთის კართან მიუსაფარი.

ორჯერ მოფრინდნენ ანგელოსები,

ამივსეს კუბო ყველა სიკეთით...

- ყოვლისმყვლეფელო, ბანკირო, მამავ,

მე უბედური კვლავ დავიქეცი!

I never lost as much but twice –

And that was in the sod.

Twice have I stood a beggar

Before the door of God!

Angels – twice descending

Reimbursed my store –

Burglar! Banker – Father!

I am poor once more!

The reader may think that it’s a pious lamentation of the poetess surrendering to her fate. And then suddenly there comes the blasphemous: “Burglar! Banker – Father!” making the previous lines sound ironical and even equivocal. Now it looks like a transaction; a Debtor appealing to her Lender. Emily’s irony takes an extremely materialistic approach towards the Lord, making God look like a business partner. This businesslike tone is reduced in the translation, however. For instance “Reimbursed my store” is rephrased to “Filled my coffin with all blessings.” Should the translator have kept the original wording, it would not sound poetic to the Georgian ear. Instead, the effect is achieved by the twist: in Georgian it goes: “Omnivorous, Banker, Father, Poor me, I lost again”, alluding to the jealous God of the Old Testament, or even Saturn Devouring His Children.

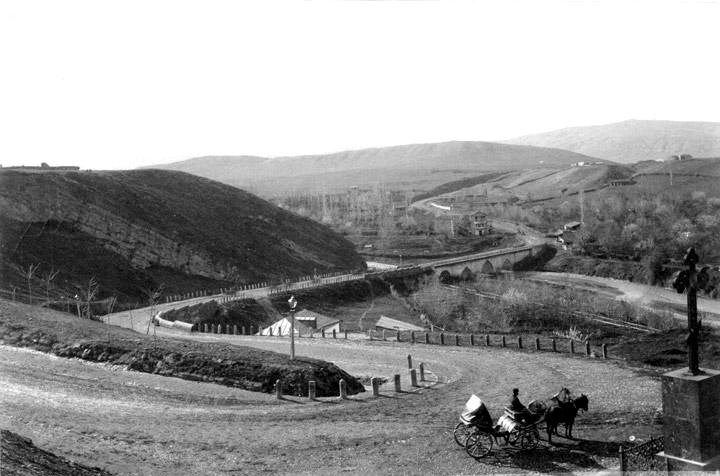

The City of Tbilisi in XIX century

There was a sinister logic in the disintegration process. Whoever planned it tried to make it the bitterest experience possible for people. Supplies of all essentials, especially food, disappeared abruptly. Tbilisi, the capital of the Republic of Georgia, with almost two million people in the 1990s, was left with no bread and no natural gas – which meant no heating. People began using kerosene and firewood to survive the winter. Permanent power failures also interfered with the water supply, especially to high-rise condominiums. The streets were full of the walking dead, joylessly dragging by with the same melancholic faces. Those who had access to food supplies suddenly turned very influential, which toppled the social order and cleared the way for all kinds of opportunism. Former Communist bosses of different calibers ran the show along with organized criminals and newly criminalized law enforcement and security officers. Apparently the strategy was to make people beg to bring back the former arrangement.

Father witnessed the dawn of the Soviet empire, a system he never accepted, but one that nevertheless created the dualistic paradigm where he existed. His attitude towards the turbulent events of those times of imposed reforms offers an interesting parallel with Emily Dickinson, from a different angle.

He published a small article in a literary gazette after Perestroika, entitled “The truth will set you free.” The article alluded to the Gospel message of freedom through conscience, which absolutely opposed the growing mainstream narrative in Georgia in the late 1980s as the Independence Movement gained the upper hand. It resonates with the Dickinson’s “My Country is Truth . . . I like Truth – it is a free Democracy.”My father saw the collapse of the old system but didn’t live to see the emergence of a new one. He died on his birthday, the 23rd of May, 1998 at 63 on the morning of the burial of my Mom who had passed away a few days before.

ის გულგრილობა, მოკვდავი რითაც

არარაობის უკუნეთს ერთვის,

საწუთროს ყველა საოცრებაზე

უდავოდ უფრო მეტია ჩემთვის -

„შინ არვარ“ - სხეულს წააწერს სული,

კარს მოიხურავს - ის დღე და ეს დღე

და ხალხით სავსე ქუჩას გაჰყვება

ჰაეროვანი ნაბიჯით ცისკენ..

THE OVERTAKELESSNESS of those

Who have accomplished Death,

Majestic to me beyond

The majesties of Earth.

The soul her “not at Home”

Inscribes upon the flesh,

And takes her fair aerial gait

Beyond the hope of touch.

The first two lines in the translation became “The Nonchalance with which a Mortal joins the Darkness of nonexistence”. OVERTAKELESSNESS translated as nonchalance, indifference, is much less expressive than the word coined by Dickinson, and the translator didn’t attempt to create an equal Georgian expression. The lines “The soul her ‘not at Home’, Inscribes upon the flesh”, are translated as “Shuts the door, Good riddance, And takes her fair aerial gait (through the crowded street, to Heaven)”. It becomes very personal, like an improvising variation inspired by Dickinson.

A hundred and five years after Emily Dickinson locked herself up in her home to explore her poetic delights, Giorgi Nishnianidze, being confronted with the same dilemmas, found an escape from the reality he never accepted. Passionate words of a lonely American woman who talked to an unknown addressee led his way to an eternity which looked more tangible than an ugly decomposed existence outside.

*

1) Isaiah Berlin, “A Note on Literature and the Arts in the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic in the closing months of 1945,” 1997, repr., Zvezda, 2003 No 7, 126–42. Published as “The Arts in Russia under Stalin,” New York Review of Books, 19 Oct., 2000, 54-63.

2) Shota Nishnianidze, a famous Georgian lyrical poet, 1929-1999.

3) He was a man of passion and never sought any personal gain. My younger brother, Constantine, was confined to home because of a severe form of epilepsy, which required the permanent attendance of my mother. Despite the person¬al hardships, Father – being true to his principles – refused to join the Communist Party although it would have meant a guaranteed career and other benefits.

4) From Emily Dickinson's letter to Joseph Lyman, quoted in Richard Sewall, The Life of Emily Dickinson, v2, (1974), 427.

*

Mikheil Nishnianidze is an interpreter, editor, and translator in English/Georgian/Russian language pairs. He writes here about his father’s and his own life on one hand, and on the other hand tries to offer an impartial view of the Soviet epoch from an insider’s prospective.