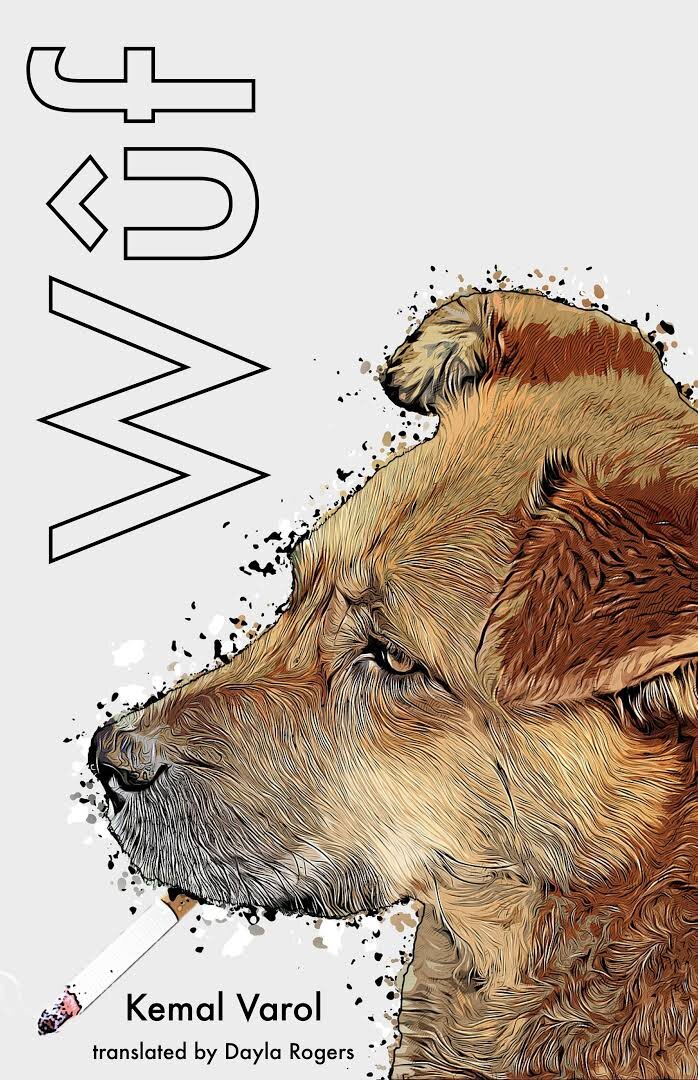

Review: Wûf by Kemal Varol

by Matthew Chovanec

Do we really believe that the human imagination can sustain itself without being startled by other shapes of sentience?

-David Abram

There is a scene early on in Kemal Varol’s novel Wûf in which an old, injured dog gets the watchman at a kennel to give him a cigarette. The dog, nicknamed Grandad, had been brought in after being found blood-soaked and with his back legs amputated up in the mountains. His fur is matted and his belly is covered in stitches, and in place of his legs are two wheels, attached to each stump. Unable to directly speak a human language, he communicates through barking.

For the first time since the day he was brought to the shelter, Grandad let out a woof, not to frighten or threaten, just to communicate. But the watchman didn’t understand...

“You want bread?” he asked.

Grandad barked.

“Those wheels bothering you?”

Granddad barked even louder.

“You want food?”

The watchman finally catches on that it is might be the cigarette that Grandad is after, and asks him to bark three times if he’s right. Grandad does so, and so the watchman places a freshly lit cigarette into his saliva-coated mouth.

There is something off about the scene when you first read it, even despite the fact that we have already been introduced to a whole cast of speaking dogs at the kennel. Off because stories with talking animals, regardless of how whimsical, are still expected to set their own fantastical ground rules early on, and then stick to them lest the illusion gets its wires crossed. We’re willing to believe in the proverbs and poetry of Watership Down as long as its characters continue hopping around like rabbits. On the other hand, we can accept the fact of Roger being framed for murder and canoodling with Jessica Rabbit as long as he doesn’t try to hop around like one. But the talking dogs of Wûf seem to renegotiate their relationship with humans throughout the whole book. With their foul-mouthed vernacular and colorful nicknames—“forknose”, “Mikrob”, “Gunsmoke” —the dogs initially seem to share some sort of insular gang subculture, like a canine version of The Warriors. At other points, they seem fully integrated into the human world as working dogs, understanding not only that they are being trained but what they are being trained for. At some points, like in the cigarette scene, dogs can communicate with humans, and are apparently entire cognizant of the human world and its simple vices. At others, dogs and humans stare back at one another in incomprehension. The dogs of Wûf are fully capable of expressing the range of classic dramatic emotions, from jealousy to heartsickness, but still lick each other’s faces and shit on the ground.

This is especially true of the novel’s many tie-ins to the regional conflict taking place in the early 1990s in the south of Turkey where the book is set. The main character Mikasa (named for a type of Turkish soccer ball) is being trained by the Turkish military as a mine-sniffing dog, and the novel is full of references to political rallies, coups, and violent confrontations with guerillas. But never once in the original book is the word “Kurd” or “Kurdish” ever used. Instead, Mikasa and the other dogs refer to the conflict as one between Northerners and Southerners. The logos and flags of Kurdish parties are described by the dogs without a clear sense of their exact political meaning. The dogs know that the bombs they are sniffing out have been left by guerillas, but they don’t know exactly why. Strangely, at one point Mikasa even mentions that the papers declare the death of twelve of them, implying briefly that beyond their ability to speak, dogs in the universe of Wûf might be able to read.

Which would all be cause for worry if the novel was in fact written as a neat political allegory of the Kurdish conflict. We could then easily guess which role the oppressed and unheard animals were supposed to be playing. From what we know of Varol–whether his obscure poetry or his eschewal of declarative forms of politics– it seems out of character to be trying to write an Anatolian Animal Farm. Politics in the novel function as a backdrop; the rugged scenery of what is at its base a simple, tragic love story. And rugged is an understatement. In his quest to be joined with his love Melsa, the dog Mikasa is cursed, kicked, muzzled, starved, shot at, and blown up by mines. The details of Grandad’s injuries as he tries to heal are terrible and vivid.

His stump, which had dragged on the ground, slowly regained its range of motion until it finally pounded the dirt and twitched side to side. The stitches on his belly came out on their own, the cuts on his back scabbed over, and his bloodstained coat began to shine anew. The only thing left were the bandages on his legs. The harness always got in the way of his attempts to gnaw them off.

This description would be familiar to many in Turkey, who have themselves been witness to acts of cruelty and extermination carried the country’s large stray dog population. Varol’s hometown of Ergani, a city in the Diyarbakir province in the south, has seen its own stray dog problems along with political violence stemming from the Kurdish conflict. The media often has stories about dogs that have been poisoned en masse, CCTV footage of dogs being indiscriminately beaten, and conversations about how to forcibly remove them from the city. A July, 2019 report on NTV claimed that the forests around Istanbul are home to more than 8 thousand stray dogs that have been shipped out from the city center, showing surreal footage of them wandering around in large groups on a deserted rural road. One resident of a nearby village claims that the city is under attack every night by roving gangs of dogs, while another details the efforts taken to bring out leftover food to the dogs in the woods. These simultaneous reactions of dread and sympathy towards dogs is a feature of daily life. The lighthearted tribute to cats seen in the recent film Kedi could easily be remade as a tragedy called Köpek.

Which is to say, as a novel offering perspective on Turkey, it would be enough for Wûf to actually just be a book about the experience and perspective of dogs. Paying attention to dogs and their lives would at the same time be paying attention to an important aspect of modern Turkish life. Whether the lady carrying bags of cat food to the alley behind her house, the New Age office worker always posting about shelter animals on her Facebook, or the pharmacist caught on camera fixing up a dog’s paw, Turkey is filled with those who have abided through the long stretch of national chauvinism and the cult of the AVM shopping mall through an ethics of care and maintenance turned towards animals. Whereas Americans treat dogs like their own pampered, unconditionally loving children, a Turkish person can see a dog in the street, living independently in the liminal space between nature and domesticity and help them without the urge to become their exclusive owner. It would make sense that they could also imagine dogs as having their own culture which only liminally fit into their own.

This alternative approach to animal empathy is a good lesson for a foreign book to make to an American reader. I admit that when I first read the book, I went looking for a definitive taxonomy of talking animals out of frustration with the cigarette scene. From classic fables to non-human sidekick movies, talking animals usually do follow one of many clearly defined tropes. But rather than taking things so literally (or figuratively, I suppose), Wûf asks us to think about the experience of dogs on their own terms. This is especially true in terms of the violence we see throughout the book. With its smoking, mine-sweeping, lusting and fighting dogs, Wûf reminds us that in their own bodies, animals are unique and remarkable, and don’t need to be analogized to humans in order to be given permission to feel. In their partial and overlapping homologies with humans, they confound our efforts to either wholly relate or wholly reject their proximity to us. Rather, the dogs of Wûf present us with a better source for empathy, an aesthetics of what Anat Pick calls the ‘creaturely’—the material, the temporal, and the vulnerable. This is an approach to animals in literature that creates connections with animals “via the bodily vulnerability –the creatureliness – we share with other animals” (Pick, 2011, p. 10). What we share is not a commensurate consciousness, but an elemental ability to feel. Thought about this way, Varol’s novel no longer seems like a strange, unsorted allegory. It comes off instead like a story trying its best to show us that dogs too have it rough, that their experience of hunger and injury is not different than ours, that they’re so alike in their feeling bodies that it wouldn’t be outrageous to think that they too might just want a smoke to take the edge off.

*

Matthew Chovanec is the English translator of Gavur Mahallesi by Mıdırgıç Margosyan and of Sinek Isırıklarının Müellifi by Barış Bıçakçı. Chovanec also recently obtained his PhD in Turkish and Arabic literature from the University of Texas at Austin.

Next: