Review: Temple of Refuge, Sartep Namiq, Bruce Sterling, Matthias Zuber, (illustrator) Felix Mertikat

By Alan Ali Saeed

Available online (free): https://www.temple-of-refuge.net/en/ (Page number in the review refer to the online version.)

This new graphic novel Temple of Refuge attempts something unusual for the medium, in telling the story of a refugee from a refugee’s point of view and it does so as a science-fiction fable. If you are interested in innovation in the subject matter of graphic novels then you will find something to enjoy in this work. If as an educator or parent you wish to make young people appreciate what it means to be a refugee, then you will also discover that this text is valuable.

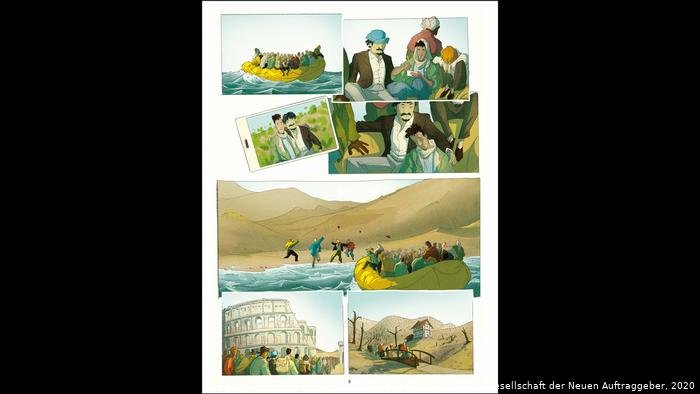

The story behind the creation of this new collaborative graphic narrative is a fascinating and innovative one; almost as much as the text itself. Sartep Namiq, a young Iraqi Kurd claiming asylum in Germany, had the original idea for the story, but it was the German division of the New Patrons (Neue Auftraggeber) society who brought Temple of Refuge to life by providing funding and expertise, connecting him with a talented team of writers and an artist. They worked with Namiq to realise his dream of creating a graphic novel while in a refugee facility in Europe. The story is written from the point of view of a migrant arriving in Europe, rather than being a text from a European perspective looking at middle eastern refugees and this makes it distinctive. For example, we see Namiq and others crossing the Mediterranean in their overloaded dingy (pp. 5-6) and arriving in Italy, where they wander through the tourist sights of Rome (Fig 1).

The refugees’ journey to Europe p. 6

The creation of the graphic novel was only possible because of the help of an unusual arts organization. The New Patrons society is a socially-minded arts charity that takes on the role of effectively organizing ‘crowdfunding’, in order to make new art happen, which they believe helps democratize the traditional role of the patron of the arts as well as assisting the artist.

New Patrons are people who want to make positive change. They commission artists to develop projects that respond to urgent questions in their city, town, or village. Since 1992, the New Patrons have assisted the completion of over 500 projects: works of art and architecture, films, music, literature, Internet projects, and theater productions.

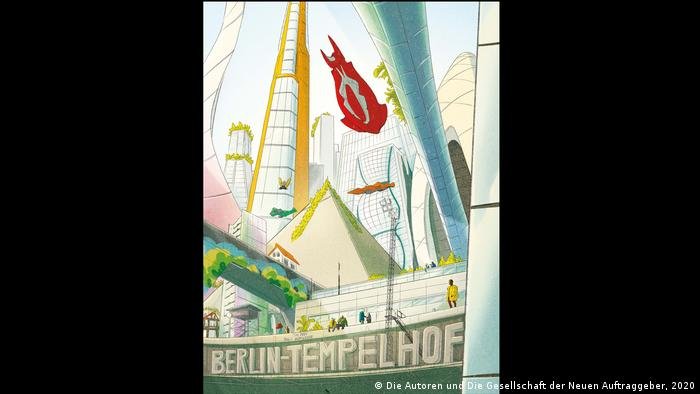

Funding also came from the Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations (Germany), the German Foreign Office and the Fondation de France. Not only did they fund Namiq’s project, but their ‘mediators’ linked him with professionals to help him create the graphic novel. Bruce Sterling is a leading SF writer (his novels include Schismatrix [1985] Islands in the Net [1988], as well as the anthology, Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology [1986]). Sterling, who has won two Hugo awards and other accolades, helped to clarify, and articulate the original idea, but it was Matthias Zuber who wrote the plot. There is no traditional dialogue as this is a wordless graphic novel. Felix Mertikat, who is known for his board game design as well as his comic art, then created the artwork. The artwork draws on the genre of science fiction for objects, such as the looming, futuristic walls of ‘Fortress Europe’ (Fig 2), but also a more cartoon-like style for depicting the humans, which reminded me of Hergé’s Tintin (Fig. 3). The artistic lineage of Temple of Refuge draws not only upon Hergé, but upon the European tradition of science-fiction graphic narrative, such as that of Moebius in his famous comic Arzach, and his edited anthologies such as Metal Hurlant. In France, comics or bande dessinée, (BD) are regarded as ‘the Ninth Art’, and they are, according to the editors of France Today (2011) ‘widely accepted as a legitimate art’.

Fortress Europe in the distance p.12

Study of the comic character "Sartep" by Felix Mertikat, 2018, New Patrons Society.

The title of the work becomes clear when we see that the refugees are housed in Tempelhof Airport — a former Berlin airport built by the Nazi regime in the 1930s – which becomes a ‘temple of refuge’. There is also a very appropriate use of vivid colours which shows how the refugee facility becomes a kind of Edenic garden, transformed by the hard work of refugee gardeners; in contrast with the dried-up lake in Kurdistan, we see at the beginning of the story. The temporary refugee camp itself is transformed by the powers of imagination and desire.

Tempelhof Airport transformed p.75

This is after all where Namiq and other refugees start with a sense of hopelessness but then feel empowered to dream of a better future in the west. I think the genre of the graphic novel might best be described as a science-fiction fable. As it is Sartep’s possession of a magic wand, in the shape of an implanted micro-chip, that enables his dreams and those of other refugees to be fulfilled. Berlin Tempelhof becomes a kind of utopian eco-city, in which former migrants and established Berliners can live together in harmony. It is a collective happy ending, not just for the protagonist but for all of the migrants.

As someone who works at a university in Sulemania, Iraqi Kurdistan, it feels ironic that we still produce our own refugees, seeking a better life elsewhere, while we ourselves generously host one of the largest refugee populations in the world. Over twenty-eight percent of our population are refugees and internally displaced people (IDP) from the wars and conflict in Syria and the rest of Iraq. Kurds are generous and if we had to take in three million Germans, then we would do it without any qualms whatsoever, returning the huge favours that Germany, (among other western countries), has done for our exiles in the past when Iraqi Kurds faced persecution. However, I can sympathise with Mr. Namiq, as many Iraqi Kurds feel we have fallen on financial, political and spiritual hard times: excessive corruption; the fall in oil prices which has devastated government revenue; wide-ranging poverty and unemployment for so many people, as state pensions and salaries have been cut or not paid due to financial difficulties; and an extremely inefficient bureaucracy which strangles the private sector. The situation is much better for Kurds in Iraqi Kurdistan when compared to those who live in Turkey, Syria or Iran, but that may be of little comfort. The dreams of the citizens of Iraqi Kurdistan have been tarnished and their hopes have faded. We seem to have lost our way. I think this is what the story means when it shows the moving images of the beautiful mountain lake drying up over the years and is not intended to be taken as literal (see fig. 5).

The drying up of the Iraqi Kurdish lake, p.3

This motif has its counterpart in the nightmarish Kurdish landscape the characters escape across, in Bakhtiyar Ali’s I Stared at The Night of The City (Reading, Berks: Periscope, 2016). Kurdish literature has long used our landscape to talk about the social and political condition of Kurdistan. Iraqi Kurds are much like the Catholic Irish once were, not fleeing direct persecution, but looking for a better life with more freedom and opportunities for personal development, away from a society that seems to have lost its way and failed to deliver. Everyone in Iraqi Kurdistan talks about being an émigré and they seem to have lost any desire to rebuild out the war-torn country. Namiq told DW in an interview that Temple of Refuge is: ‘a modern fairy tale’. He said: ‘But why not dream of a place where everyone has the same opportunities, whether they are rich or poor?’ This is, of course, a somewhat idealistic view of the reality of the west with its inherent structures of social class and race, but nevertheless, it is one that many Kurds share. The reader will sympathize with Namiq.

The text itself is a fantastical one, but also wordless, playing instead to the possibilities offered by an entirely visual narrative. This allows it to communicate more easily across cultures, as it would not if it were in Kurdish or even German. However, it also speaks to the fact that, as a refugee, the protagonist feels himself without words, in a new culture, and perhaps because refugees speak so many languages and the text seeks to gestures towards this situation. There is some excellent storytelling here in terms of panel layout. The aim of improving the public perception of refugees is a good thing, and I can see how this would be a useful text in schools and colleges. Moreover, I enjoyed reading this much more as a reader than I thought I would, bearing in mind the concept of a Kurdish refugee becoming a ‘superhero’ sounded a bit self-regarding, even with such worthy intentions behind it. While it is true that the symbolism may be too overt and obvious for some, this is after all a graphic novel and such symbolism is typical of the genre. I found Temple of Refuge inventive, clever, creative, and quirky and it certainly adds something new to the tradition of science fiction comics and graphic novels.

*