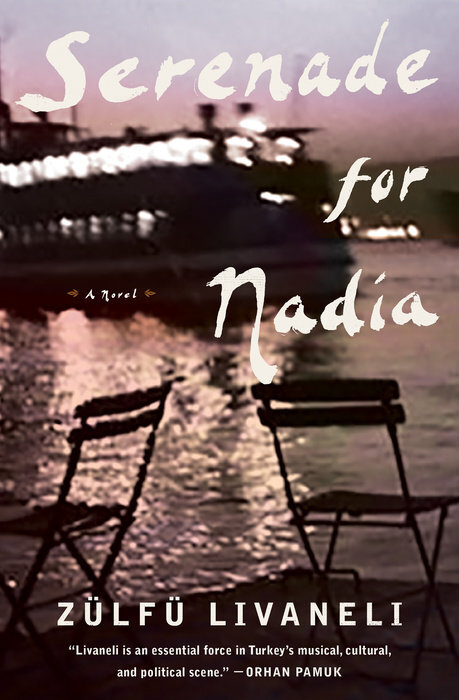

Review: Serenade for Nadia, Zülfü Livaneli

By Luke Frostick

On the 24th of February 1942, a Soviet submarine torpedoed a ship, The Struma, in the black sea just outside the mouth of the Bosphorus. On board were 800 Jewish refugees fleeing the nazis via Romania. All but one of them drowned. The ship was bound for the middle east, but the British, to keep the fragile peace in Palestine, had refused to let it sail on and the Turkish authorities didn’t allow the refugees to disembark in Istanbul to keep their neutrality with the British and the Nazis intact. It was one of the most avoidable tragedies of the war.

Zülfü Livaneli used the tragedy as the backdrop to his newly translated novel Serenade for Nadia. The majority of the events take place in 2001. The novel follows Maya Duran an assistant at Istanbul University fast approaching burnout, trying to raise a troubled son and get alimony money out of her ex-husband. She is given the job of looking after a Harvard Professor Maximilian Wagner who is returning to Istanbul after a long absence. He seems to have some connection with The Struma. Through the course of the story, Maya works out Maximilian secrets, this history of The Sturma all the while pushing back against family members and state officials who would all prefer that the past stayed buried.

This is a great premise for a story. However, the actual novel doesn’t quite live up to it. The mystery surrounding Professor Maximilian is quite easily solved by both the reader and the protagonist. Moreover, some potentially interesting sections are raised early in the book, where Turkish secret agents and members of the British and Russian consulates try to investigate the professor, but they don’t really go anywhere. Additionally, you never feel that the protagonist is in any danger from the ominous and powerful people that are suddenly taking an interest in her.

It could be argued that the point of the book wasn’t to be a mystery thriller, but a more contemplative tale about love and how by embracing the past not covering it up, we can find a sense of freedom. However, it all wraps up pretty quickly and the latter parts of the book are more concerned with a scandal at her university that, although it is connected to the professor -sort of- doesn’t tie in with the themes of the story feels like it is there to artificially raise the stakes.

That being said, the relationship between Maya and Maximilian feels authentic and the way that she grows through the experience is interesting and didn’t quite go where I was expecting it to go, which was nice.

The prose is functional but does not shine particularly. This is disappointing because Livaneli has a reputation as a poet and a musician, so I had hoped for a bit of that to be carried over to the book. (unrelated note: If you want to treat yourself, you should listen to some of Livaneli’s music. I recommend you start here.)

The area that the book is most remarkable in, is its thematic content. The book is all about how history is buried by the powerful and how states of all sizes are capable of terrible things through combinations of carelessness, calmness and laziness. This is a fine enough message for any nation on earth, but it particularly resonates in the Turkish context, which is where Livaneli is really interested in exploring.

The three central women of Maya’s story are all hiding their routs and their identities due to horrible atrocities committed against them and their people.

Maya had become Ayse, Mari had become Semahat and Nadia had become Deborah.

Livaneli posits that this concealment of history of origin is damaging, not only to an individual but to society. Turkish people, even more so than a lot of nationalities, have complicated lineages that stem from all around the Balkans, the middle east, Anatolia, the Caucuses and beyond, but those lineages are often unknown or hidden.

One of the most striking examples that Livaneli gives is that Maya has an Armenian grandmother and the revelation of that fact has caused a schism with her military brother who does not want his Turkish-ness to be called into question.

At first, he refused to believe me. Then after I showed him the birth certificate his face went white and he muttered something about our blood being tainted.

Explicitly linking the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust, if only contextual, is a bold move given that some in Turkey still regard writing about the Genocide as a crime. The book also talks about other instances where the Turkish state was involved in or failed to protect both Christian and Muslim minorities. The book’s purpose is not to simply list off a sequence of atrocities that happened in Turkey. It is more to push back on the narrative put forward by Turkish nationalists of Turkey as the nation of the Turks. He wants to remind readers that Turkey has a far more complex heritage that includes Turks, Kurds, Circassians, Bosnians, Armenians, Jews, Alevis, Laz and Zaza and that, like the protagonists, there is value in exploring heritage because you never know what you will find there. In Livaneli’s own words:

How much better it might be if we’d all been allowed to be who we are if we had been free to build a multiethnic, multicultural society. We’d been so imprisoned by the nationalist myth promulgated by those who felt they had to create a national identity. Yet the myth was so fragile that those who felt their existence depended on it had to resort to violence.

The only critique I have for Livaneli’s work in this regard is that there is a lot of history to cram into a novel and sometimes it breaks the flow of narrative and is a little exposition-heavy.

This is a book that aims high and doesn’t quite get there. Its fascinating thematic and historic aspects are undermined by an underwhelming plot.

*