On the advent of illiberal democracy: Gideon Rachman’s “The Age of the Strongman”

By Matt A Hanson

In the current zeitgeist, while strongmen rule some of the world’s most powerful governments, the idea of democracy must first be qualified by whether or not it is liberal. A league of strongmen have emerged at the center of global affairs in the last two decades, indebted to the rise of populism, propped up by personality cults that encourage misinformed populaces who fear elitist corruption by liberals and political displacement by minorities and immigrants.

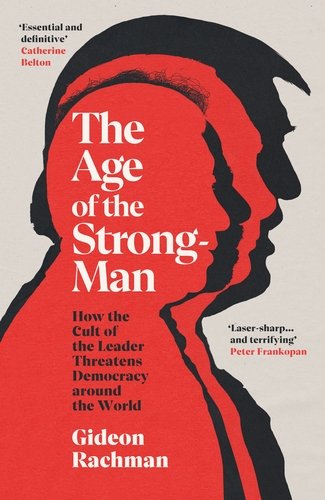

The invention of illiberal democracy, in turn, has been promulgated chiefly within the EU by Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, and less glamorously by Jarosław Kaczyński of Poland, according to senior Foreign Affairs columnist Gideon Rachman. His new book, “The Age of the Strongman”, published on April 19 by Other Press, offers thorough, often firsthand biographical accounts of every major national leader around the globe, focusing on what makes strongmen strongmen.

About a third of the way through his book, Rachman slides from the right to the left when unveiling the horrors of strongman politics. But leftism, in that sense, can not be equated to liberalism, nor can either be seen as an ally to democracy. For example, Hugo Chavez won democratic elections for president of Venezuela in 1998, and then “followed a textbook pattern of strongman rule”, Rachman wrote, listing Chavez’s credentials as a self-serving xenophobe.

“The Age of the Strongman” dedicates a chapter to one or two strongmen at a time. He begins with takedowns of Vladimir Putin, but his irreproachable critiques of deplorable figures like Rodrigo Duterte and Donald Trump become murkier as his focus homes in on Latin America, comparing presidents Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil and Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico, simply because they are, as he wrote, both nationalists, and religious.

In perhaps the unlikeliest of targets in the book, Rachman refers to Amlo, as Mexico’s president is universally known, as “Castro-like”. Like most strongmen, his hold on power came under a peculiar degree of strain due to the pandemic. It could be said that the Trump presidency and Covid-19 were the single-most defining factors in cementing the reign of strongmen whose cross-border alliances are tempered by their conservative domestic policies.

Despite their tendencies toward the left or right, as Rachman argues, strongmen are first and foremost illiberal. And the legitimatization of illiberality has appreciated its political capital following Trump's years in office. Each and every strongman that Rachman denounces and investigates, interviews and historicizes is contextualized in terms of Trump and his lies. Rachman wrote that Bolsonaro was Trump’s “ideological soulmate” concerning voter fraud.

Although he called Trump fascist while campaigning for his presidency, Amlo eventually supported his claim to a stolen election in the wake of the Jan. 6 insurrection of 2021, a move that Rachman explained was likely a reflection of his own turbulent rise to power, facing many defeats along the way. Amlo is expected to follow in the footsteps of Xi Jinping and Putin, personalizing his rule by making it all about him, extending the length of the presidential term.

The pandemic effectively unseated Peru’s Penn-educated president Francisco Sagati for the left-wing populist Pedro Castillo. In Brazil, while Bolsonaro’s heavy-handed conservatism may have lost the country lives, his strongman bluntness preserved the economic backbone of its political order, its illiberalism intact. Rachman traces the history of regions and blocs prior to the strongman era, noting how the liberalism of 1980s Latin America is now a fading memory.

What sets Bolsonaro and Amlo apart is the narrative arc of their distinct appearances within the Western liberal discourse, which, arguably after the fall of the Soviet Union, has hoped desperately and mostly disappointingly, for allies on the course toward democracy. But what Rachman is identifying is that there is a global recession of democracy, its institutions and values increasingly crushed and coopted by illiberal populists from both the right and left.

On a number of occasions, Rachman names the heads of state of Russia, Turkey, China, India and Hungary as examples of strongmen who, in their first years in office, demonstrated a record as liberal reformers. Each, in their own way, were sanctioned by Western powers. Electoral democracy and its traditions of civil society seemed to work. But what strongmen have since demonstrated is that they can use it to work for them, too.

In his chapter on Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Rachman quotes the strongman: “Democracy is like a tram that you ride, until you get to your destination”, which he wrote in a piece for The Economist in 2016, just months before the attempted coup skyrocketed him into godlike status. Erdogan, like Narendra Modi and many strongmen, rose to power on a masculine hero myth, ascending beyond his humble origins with an anti-establishment streak.

As the new millennium has seen liberal reformers transform into the illiberal strongmen known infamously by their last names in connection with the nations that many have ruled for unprecedented terms, Western pundits might have learned. “On the contrary,” Rachman wrote, "it may have made Western opinion-formers even more eager to find champions of liberal democracy in a world in which strongman authoritarianism seems to be on the march."

The vicious circle of cheerleading foreign policy into a resurgence of liberalism has played out with particular clarity at the World Economic Forum in Davos, with Rachman often in attendance watching as audiences applaud a leader one day in the name of democracy, while condemning them the next after they’ve taken advantage of its empowerments. Such was the case in response to Ethiopia’s Abiy Ahmed.

Unlike initially flattering comparisons to Gandhi, Mandela and Gorbachev, Rachman echoed the concerns of British journalist Michela Wrong, who saw Ahmed as more like Trump, Putin and Erdogan, exploiting democratic processes to promote the strongman’s preferable brand of combative nationalism. Although of mixed ethnic and religious descent, and a speaker of Tigrayan, Ahmed went to war with Ethiopia’s Tigrayan minority.

War, like nothing else, weaponizes democracy to kill liberalism. Rachman noted that more than a case of the 21st century strongman, Ahmed’s rise and fall as a pro-democracy liberal in Western eyes is also common among postcolonial political narratives in Africa in which “liberation heroes” become “authoritarian despots”. Rachman went off course from the present in his chapter on Africa, retelling the story of Robert Mugabe as a prototypical strongman

In the aftermath of Mugabe’s infamy, as the politician Emmerson Mnangagwa succeeded him, the billion Zimbabwean dollar question remains: If democracy is a means to power, and power corrupts, does democracy corrupt? To an intelligent observer, it might seem obvious that democracy itself is unable to clarify the complexities involved in how a national society distributes its public wealth in all of its forms.

But the simplistic assessment of democracy itself, as a liberal ideal, is a weakness that strongmen exploit, as they erode democratic institutions with a political savvy that is unique to the 21st century in which social media draws a direct line between rightwing politicians and their constituencies weary of traditional media. While Russia and Turkey jail journalists, as China censors the Internet, strongmen like Trump and Bolsonaro turned to old-fashioned lies.

Rachman’s book is full of colorful anecdotes. Joseph ‘Erap’ Estrada, the heavy-drinking former president of the Philippines fell asleep during one of his interviews. Bolsonaro fired his minister culture for plagiarizing a Joseph Goebbels speech. Kaczynski chose to live with his mother over the state residency while ruling Poland. Rachman described Putin answering journalists at Davos as a “masterclass in destruction and bullying”.

Putin’s reputation is repeatedly examined in “The Age of the Strongman”, as the apotheosis of illiberalism. Rachman quoted oligarch Konstantin Malofeev to capture how Putin sees liberals: “No borders between countries and no distinction between men and women.” But in the presence of Clinton, he was seen in 2000 as someone who would respect Russia’s rule of law, later enjoying praise from George W. Bush and other Western leaders until he invaded Georgia.

The first war in Europe in the 21st century occurred between Russia and Georgia in 2008. And less than two decades after the Cold War ended, Soviet territorial disputes continue. In light of current events, the gospel of the strongman is being heard loud and clear as Ukraine suffers Russian bombardments that would seek to topple its electoral democracy in the midst of the Kremlin’s armed conflicts since 2014, following their annexation of Crimea.

In the age of the strongman, Ukraine is an endangered bastion of sovereign, liberal democracy. Elsewhere, confidence in democracy is reduced to petty illusions. The global erosion of democratic principles comes with the erosion of confidence in its core ideals. That is true in the West, as Rachman wrote, and increasingly in Africa, leaping from a quarter to a half of respondents in the Afrobarometer network saying they are dissatisfied with democracy itself.

In his constant comparing Rachman can taper out when he might have narrowed down arguments that, at times, seem overly general and even dismissive. When discussing the effect of identity politics on democracy in the U.S. and Africa, he writes of how “…in the wealthy and powerful United States, identity-based politics has become a powerful enough force to threaten the country’s long-established democratic structures”, but stops there about the U.S.

Tracing the origins of strongman politics in Africa, Rachman critically spotlights dirty dealings with China, whose leadership is unconcerned with the promotion of liberal democracy as part of its capitalist exploits abroad. In fact, China has a track record for reinforcing autocracy and the genocidal crimes against humanity its regimes perpetrate, such as when Chinese lobbyists attempted to persuade the International Criminal Court not to indict Omar al-Bashir.

In 2007, the value of Chinese trade with Africa, measured in billions of dollars, was three times more lucrative than with the U.S. And politically, Chinese influences in the field of education, imparting scholarships to study in China, for example, have a more nefarious, illiberal edge, mutilating democratization efforts. With China’s obscene history of genocide in Xinjiang and Tibet on the books, its exportation of surveillance technology is of deep concern.

Strongmen thrive on extrajudicial, cutthroat competition against their political opponents, destroying dissent by any and all means so as to preserve power for life. While this appears to be in direct conflict with the very definition of democracy, the age of the strongman reveals how fragile and vulnerable democracy is to the exploitation of nationalists who use governmental institutions, the military, every apparatus of state power in their personal interest.

Rachman is emphatic when it comes to progressive responses in the interest of preserving what is left of democratic liberalism, values like social pluralism and rule of law. The issue of migration is arguably the most difficult piece of the puzzle. As Africa expects its population to double in the next thirty years, that means another 1.2 billion people will grow up in nations where outmigration to Europe is one of the more viable means of socioeconomic mobility.

And those who have most vocally supported the integration of national society into the internationalist future are France’s Emmanuel Macron, a climate change advocate who describes himself as an ardent globalist, and Germany’s former chancellor Angela Merkel, whose spartan residence in central Berlin stood in stark contrast to the pomp of strongmen and their masculine penchant for palatial displays.

In Turkey, Erdogan’s decadent, religious populism is an act of cognitive dissonance. And as perhaps the most contentious state with regards to EU accession and the migrant crisis, Turkey’s strongman rule forced the EU to compromise its values as Germany's neo-Nazi party Alternative for Germany (AfD), became the largest political opposition. Strongmen flocked to its anti-immigrant platform, like Orbán of Hungary, bringing illiberal democracy to Europe.

While discussing the liberal, democratic leaders of France and Germany, Rachman notes that, like many commentators’ disbelief in Trump, Merkel was also condescendingly skeptical of Putin. He was “a figure from the nineteenth century” to her, until he attacked Ukraine in 2014. As Crimea’s Russian annexation preceded the peak of the refugee crisis, followed by Brexit, the EU was tested. And as Russia continues to invade Ukraine, all bets are off.

What the EU and Russia know well is how erratic American leadership can be, with Biden a temporary reprieve from the strongman bent that reshaped the world order. In the event of another American strongman parallel to Putin’s aggressions, the fragility of liberal democracy could shatter into a million, dangerously sharp pieces, leaving continental Europe, again, as in World War Two, in a precarious balance, its influx of Eastern European refugees in the crossfire.

“The Age of the Strongman” comes after Frank Dikötter’s “How To Be A Dictator” (2019), within a liberal chorus against the dissonant work of rightwing intellectuals who have gained footing in the populist persuasion. Among illiberal readers, Rachman noted a few required readings, such as Yoram Hazony’s “The Virtue of Nationalism”, “The Great Replacement” by Renaud Camus, or Trump’s 1990 Playboy interview.

In the 21st century, as strongmen have come to the fore, liberals might turn to classics like “The Open Society and Its Enemies” by Austrian-born philosopher Karl Popper, which influenced George Soros. “The Age of the Strongman” devotes a biographical chapter to the Hungarian philanthropist hated by conspiratorial strongmen. In Erdogan’s Turkey, his influence is directly linked to the fate of political prisoner Osman Kavala, who has remained in jail since 2017.

Rachman’s comparison between Soros and Steve Bannon goes down a rocky road, one which tries to unpack the essence of illiberal democracy, which might be understood as a rejection of universal values so as to protect a local version of ethnocentric nationalism. Echoing the strongman convictions of Erdogan, Rachman wrote: “Since the preservation of a particular civilization is paramount, democracy is only valuable to the extent that it furthers this goal.”

And whereas Soros saw the Holocaust as the destruction of liberal Europe, so there is a widespread academic resurgence of Nazi theorist Carl Schmitt, with his “Oxford Handbook” published in 2017 by Oxford University Press, reread from Harvard to Beijing, where it has planted very firm roots. For Soros, Rachman and many likeminded pundits, China raises the biggest threat to liberal democracy around the world. It is the strongman’s den.

Ending with commentary on Biden’s presidency, considering his withdrawal from Afghanistan and the fact that he will be 82 ahead of an uncertain 2024 reelection with Republicans almost sure to support Trump again, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is testing the world’s faith in liberal democracy. As Rachman wrote: “The world has reason to question whether the US, as a whole, still has the energy and means to fight for liberal democracy around the globe.”

When it comes to identifying the age of the strongman as an era in history, in many ways novel while clearly derived from imperialist momentums like Nazism, Rachman finishes his repetitive, but well-founded book with confidence in the liberalization of democracy, and for all of its erratic politicking, America, asserting, finally, that strongmen states are futile, unstable illusions of national strength. The present empowerment of Russia and China, then, might just be another long night for the liberal soul.

*

Next: