Luke Frostick, Editor in Chief

(Deadline connoisseur and commissar)

So another month another edition of the BROB, we’ve got a good one this time full of fantastic work in every section. As usual the biggest thanks to everybody who made it happen, the fantastic editors, the talented writers and poets who put their hearts on the line when they submit their work for publication.

Special thanks to our cover artist Najat Sghyar, who sat down with us in our secret editing café to go over her designs, they were all great and it is a shame we can only use one. You can find more of her work here.

In some ways these editorials are getting harder to write because the magazine is running so smoothly so in the next edition I'm going to try out a new format here. You will all have to wait and see what that's all about.

I really don't have very much more to add except enjoy.

Erica Eller Editorial and Outreach Assistant

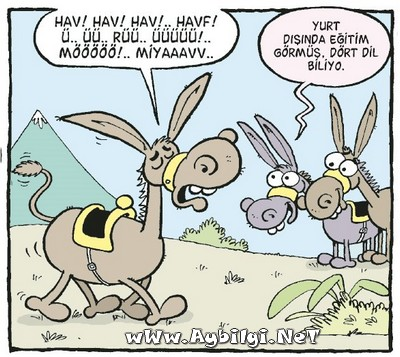

There's a Turkish comic in which a donkey speaks the languages of dog, rooster, cow and cat (see below). His eavesdropping friends think he must have studied abroad because he now speaks four foreign languages. A lover of languages myself, Najat's cover art captures our own collection (I dare not call it a bestiary!) of tongues in Istanbul, and the work in BRB ceaselessly reflects this as well.

In our interview, Shruti Swamy mentions how she inherited the playfulness of her father's punning, musical mutlilingualism. This goes to show that foreign language can even lie beneath our most familiar thoughts and words (which, for me, are in English). Grammar and vocabulary aren't all that make up a language. The rhythm, breath, and cadence, too, bring life to the reductive terms of structuralism: the signifier and the signified. Such terminology can't capture the beauty of comedic timing, the etymological history of our words, or the tenor of emotion that language hides behind a string of words. That's why I was thrilled to discover Elif Batuman's subtle linguistic play throughout her novel, The Idiot, in which she more or less translates the feeling of the Turkish -mış suffix into English, as I've written about in my book review. Likewise, with English as my mother tongue, I'm constantly bombarded with new turns of thought by living amidst such a thriving bounty of linguistic richness in Istanbul.

After just a few months, I've finally managed to convince my boyfriend to contribute his literary talents to our journal. Alptekin Uzel's book review touches on the French influence among writers and intellectuals of the early Republican period. Not only was Paris seen as the cultural capital of the world at that time, it was also led to the circulation of lo-brow detective novels by way of translations made a well-respected, high-brow Turkish author: Sait Faik. Istanbul itself is constantly set in literary texts as a backdrop for thrilling detective narratives and perhaps that speaks not only to the way language migrates, but also to the way that literary genres translate with ease.

As you can see in Najat's cover, the Gran Rue de Pera recalls the old French name of Istiklal street. Through this lens of translatability, we also associate different languages with different time periods in Istanbul. The remnants of Greek culture in Istanbul remind us of the Greek-Turkish population exchange that occurred in the first year of the new Turkish republic, making it hard to see where one culture ends and another begins. Such complications are touched upon in the fascinating discussion of Jewish cultural migration that Matt Hanson provides in his creative non-fiction piece. Through it, we can see that migrations may be balanced by later returns, the same lesson taught by the Odyssey referenced in its title. Such is also the case for the intriguing coat that circulates in the creative non-fiction piece, "Being Human."

These are just a few of the pieces that I worked closely with in terms of inviting contributors and writing, translating, and proofreading texts for this edition. It was all a labor of love.