Japan has an incredibly deep literary tradition from old school classics like Natsumi Soseki to pulp and gore writers like Ryu Murukami. However, it can be a little bit intimidating. Jay Rubin’s anthology of Japanese short stories is a fantastic place to start. With a wide range of authors from mega famous to the relatively unknown, this anthology provides a great introduction for beginners and plenty of new material for Japanophiles. I spoke to Jay Rubin about this new collection of Japanese fiction.

Luke: Could you start by telling me a little bit about yourself and how you became interested in Japanese literature?

Jay: I was a second-year undergraduate at the University of Chicago in search of some kind of non-Western course before I committed full-time to a major in English or philosophy and wouldn’t have room in my schedule for electives. By chance, there was an introduction to Japanese literature available, and I wandered into it. This was 1961, and I’ve been stuck in Japanese ever since. I started studying the language that summer because the professor, Edwin McClellan, convinced me that no translation could substitute for reading in the original. He was right.

Luke: Japanese literature has quite a large global reach. Here in Turkey names like Murakami, Tanizaki and Kawabata are well known to readers. Why do you think Japanese books have such a large global appeal?

Jay: I’ve been immersed in Japanese literature so long, I can’t answer that question with any objectivity. In the English-speaking world, translators such as Edwin McClellan, Edward Seidensticker, Howard Hibbett and Donald Keene did such a great job of introducing Japanese literature to the reading public, it quickly outgrew its initial niche readership.

Luke: What made you want to put this anthology together?

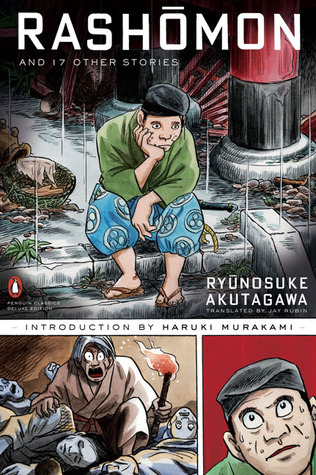

Jay: The project was suggested to me in 2013 by the marvelous Penguin editor Simon Winder, with whom I had worked on Rashōmon and Seventeen Other Stories and Sanshirō. I was initially hesitant to plunge into such a gigantic body of works but soon realized that my fifty years of work in modern Japanese literature had given me a pretty good backlog of stories I truly loved, and that if I concentrated on those (rather than a selection of established masterpieces that didn’t really interest me), I wouldn’t have that much trouble filling the pages. As it turned out, the anthology is nearly a hundred pages longer than what Simon originally asked for.

Luke: What I liked about the anthology, beyond stoking my love of all things Japanese, was how the short stories in the book are excellent examples of the form. Each one has what I would describe as complete narrative and character arcs depicted in very limited word counts. The book really shows the capability of the short story, which I often feel is neglected by writers who focus on the novel. To what extent was this part of your thinking when you were making your selections for the anthology?

Jay: You have perhaps here answered your own second question. Short forms have always dominated Japanese literary expression (think, haiku) and have played a major role in the modern literary industry, which centers on a good number of excellent literary journals. In other words, standards are high and writers get a lot of practice. I often feel that literary criticism involves rationalizing the importance of literary works that are fundamentally boring. I didn’t want stuff like that in the book. These stories work.

Luke: There are a lot of very famous authors in the book, from classic writers like Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki and Natsume Soseki to modern writers like Haruki Murakami and Banana Yoshimoto, but there are also some less famous writers who I don't think I’m alone in having never heard of. Which one of these writers are you most excited to have published in the book?

Jay: Tomoyuki Hoshino’s piece is almost suffocatingly intense on wartime hysteria, and Yuten Sawanishi almost succeeds in convincing you that it is possible for people to die by “Filling Up with Sugar.” Don’t get me started, though. I’ll name them all. Yuichi Seirai’s narrative is amazing in its combination of traditional Nagasaki crypto-Christian culture and intense eroticism—an eye-opening piece for any American who does not know what our atomic bombs did to the people on the ground.

Luke: Are any of the stories in translation for the first time?

Jay: Several of them have appeared in academic or other publications with limited circulation, but six are brand new. You will probably think of “In the Box” every time you get on an elevator. “Bee Honey” will probably come to mind whenever you hear of the “disappeared” in Argentina and other oppressive regimes. “Factory Town” will probably make you laugh out loud before you start worrying about air pollution.

Luke: Which of the writers included in the book would you like the see more widely translated and read?

Jay: Fortunately, there is already a volume of stories by Yuichi Seirai, the Nagasaki writer. I’d like to see more of the younger writers I mentioned above. I was lucky to have met Yuten Sawanishi almost by chance, am pleased that reviewers tend to mention his startling story as one that made a big impression on them. He wrote one novella set entirely in Belgium, with no Japanese characters, in which the women of the village suddenly start turning into flamingos.

Luke: There were some writers I was surprised to find not included in the book, Kōbō Abe and Kenzaburō Ōe for example. Were there any stories or writers that you would have liked to have included in the book, but were unable?

Jay: I wanted to include John Nathan’s brilliant translation of Ōe‘s “Teach Us to Outgrow our Madness,” but I already had too many long pieces in the book. I’ve never been that crazy about Kōbō Abe, who is too cool and distant for me. My original proposal to Penguin had 28 items, only 13 of which survived to be among the book’s final 35. I tried to make up for eliminating so many writers by providing a six-page list for “Further Reading“.

Luke: The book has a lot of different translators. Translation is more subjective than I think a lot of people realise and the choices made by translators matter in how the final text reads and feels, particularly with languages so different to English. Did you seek consistency from your translators or were you happy to give them freedom to use their own styles?

Jay: Several of the stories are in there precisely because I felt the translations were so successful, but that didn’t stop me from checking each one line-by-line for style and accuracy. I contacted each of the (living) translators regarding my suggested revisions and got enthusiastic responses in most cases. In fact, my correspondence with the other translators was one of the most enjoyable aspects of the project—mainly, I think, because they saw I was trying to help them improve their work, not impose uniformity on the collection. My linguist friend Shosaku Maeda was tremendously helpful in the checking process.

Luke: In the anthology, you rejected a chronological approach, rather choosing to divide the book into different themes. What led you to take this and how did you select the themes?

Jay Rubin

Jay: Early on, while I was still assuming the stories would be listed chronologically, I thought I’d like to end the collection with literary reflections of the Fukushima disaster of 2011, but when I started thinking about an actual historical disaster, it occurred to me to combine those stories with other disaster stories of the modern era, and once “Disasters, Natural and Man-Made” came together, it seemed natural to group the stories by theme or mood—put all the funny ones together, and all the stories of male-female (or female-female) relationships, etc.

Luke: Are there any other anthologies of Japanese short fiction that you could recommend to readers who want more (e.g me)?

Jay: See “Further Reading” on pp. xxxix-xliv. That should satisfy anybody.

Luke: I’m in the process of putting together an anthology of my own, though much more limited in scale that yours. I have found the most difficult part was not in fact getting the copy editing and translations done it has been all the publishing side of things getting rights, etc. that I am struggling with. What part of the process did you find the most challenging?

Jay: Following the advice of good friend Ted Goossen, editor of The Oxford Book of Japanese Short Stories, I accepted the project only after Penguin agreed to handle the busy work of rights and permissions and payments. I did have to get involved in a few cases where they had trouble contacting Japanese authors or agencies, but another good friend, Motoyuki Shibata (renowned translator of American fiction and author of the story “London Circus”), came to the rescue there. I had all the fun.

Luke: If you could give a piece of advice to people thinking to put together similar anthologies from different countries round the world, what would it be?

Jay: Work with a supportive publisher like Penguin or stick exclusively with public domain works.

Luke: I like to finish my interviews with this question, what are you reading now?

Jay: The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain, by Maria Rosa Menocal.