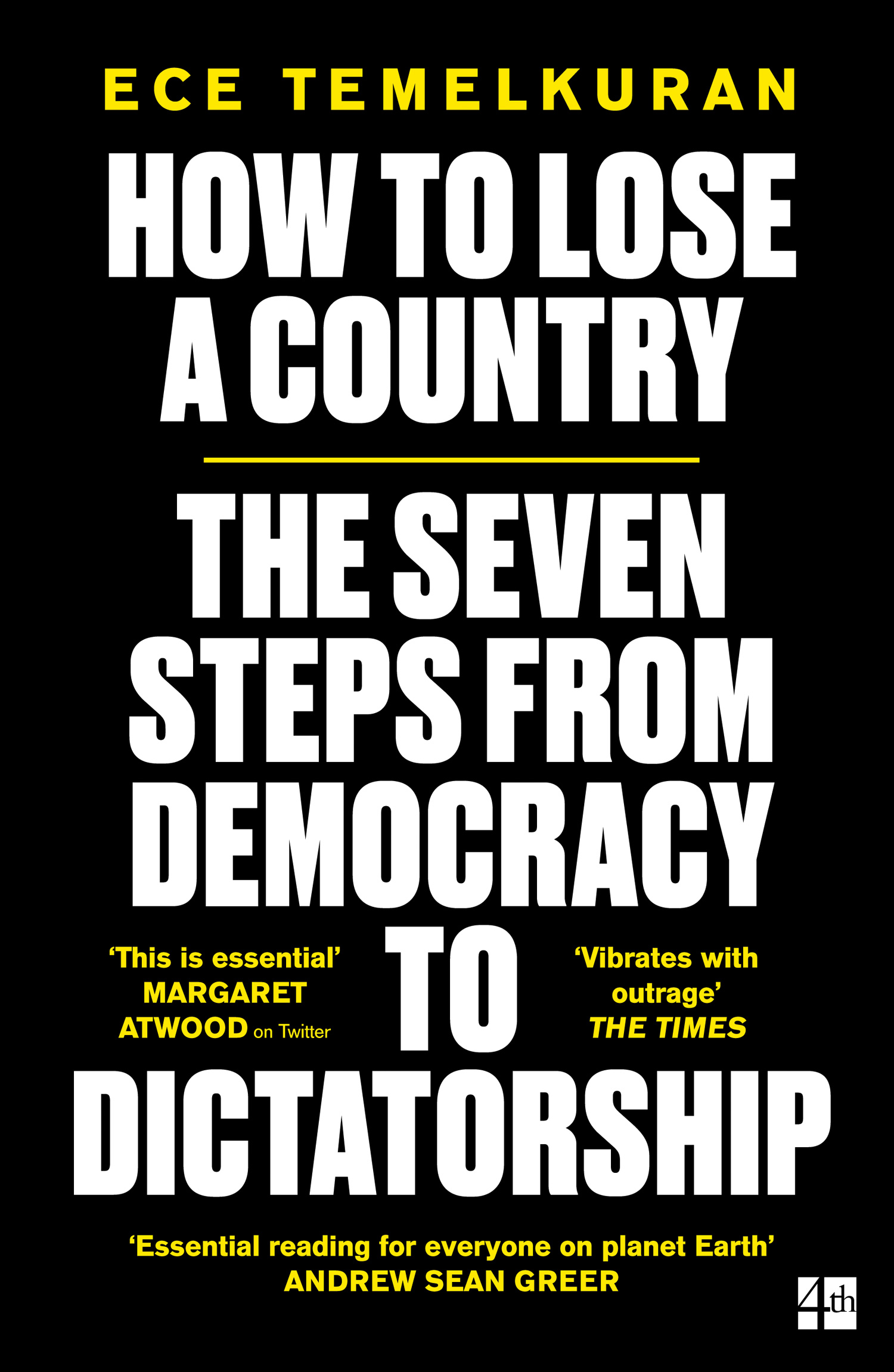

Ece Temelkuran is an award winning journalist and novelist whose latest work, How To Lose A Country: Seven Steps from Democracy to Dictatorship, is a bold book that traces the decline of Turkish democracy and warns that these processes are becoming an international phenomenon. You can read my review of the book here. In the meantime, Temelkuran has very kindly agreed to talk to us about authoritarianism and populism - a topic that is, unfortunately, more important now than ever.

Luke: I would like to start by defining some vocabulary. What exactly do you mean when you say ‘authoritarian’ and ‘populist’? Are those two always linked?

Ece: I mean they are the two faces of the same coin. Populism is a political tool to mobilize and politicize ignorance and indignity to manipulate the masses, to make political and moral choices completely against their own interests. Authoritarianism is what comes after the masses start removing their consent from the status quo; oppression, fear, indignity. However an autocrat is always obliged to use populist tools.

Authoritarianism and populism are always linked. These are two political tools that support each other. But then, when authoritarianism takes full charge of a country, the populist techniques become less and less necessary. Authoritarian regimes use populism in order to manufacture consent whenever they feel it is necessary.

Luke: Through your research, what are the most striking similarities between the different authoritarian leaders and regimes round the world?

Ece: There are seven of them and those seven similarities have become the chapter titles of How To Lose A Country. However, one can always add to those commonalities. We are in the middle of a brand new political process as a globe and we are all trying to understand what is happening to us. The book I guess is open to contribution in that way. I can say that How To Lose A Country is an organic book that invites people to think and add their experience to my thoughts. Among the seven similarities there is one that is particularly important to me, which is the loss of shame and how it became possible thanks to neoliberal politics; “Immorality is the new black”.

Luke: In what important ways do they differ?

Ece: Naturally, every country has its own historical, political and cultural complications. If we make an attempt to count the differences, that would be an infinite process. What we need at this point is not the differences but the similarities in order to reverse the current of authoritarianism. During the book launch events in several countries I noticed that one of the reflexive reactions to the book has been to focus on the differences of the countries. Well, I believe that it is only repeating the obvious, therefore a waste of time. What we need at this point is solidarity and enumerating the differences does not help our case. What would help us is to understand the main logic, the fundamental mechanism working behind all this confusion and noise.

Luke: Which of the major democracies do you think is at the greatest risk of an authoritarian take-over? Is it Mitch McConnell’s America? Brexit Britain? Or is it somewhere less obvious, like politicly stagnant Japan?

Photo by Kristina Krepela

Ece: This is a global wave and we are all under the same risk. However, it is quite gobsmacking to see that Britain and the US, that are considered to be the most matured democracies, could not hold as long as Turkey did. Our authoritarian leader had to struggle with democratic forces for years in order to meddle with state institutions, whereas for Boris Johnson or Trump, it took only a few weeks. That is a pity. But also, it is a fact that proves my analysis of fascism; no liberal democracy is immune to fascism for the reason that the neo-liberal system has in fact stripped them of the central idea of social justice.

Luke: You place a lot of the root causes for authoritarian backsliding at the door of neoliberalism. Could you walk me through that argument?

Ece: Very briefly, neoliberalism imposed a certain set of values and a political perspective, which can be summarized with TINA, “There is no alternative”. By doing so, it turned the citizens into political objects who are inconsequential when it comes to democratic processes. What makes an autocrat drool is individuals who are ready to give up their right to determine their political faith and believing that the freedom is limited tothe consumer’s freedom of choice. We are now witnessing the extreme consequences of this understanding of politics. Therefore Trump, Boris Johnson even Putin are not evil exceptions, but actually they are only the perfectly shaped personas of the neo-liberal politics and ethics.

Luke: Do you think that, since the fall of the Soviet Union, we have take liberalism for granted? Have we forgotten how to make the case for liberalism and democracy itself?

Ece: I would go a bit further back to the beginning of 20th century to pinpoint the place where we started going down the hill. The zealous fight against the idea of social justice is the fundamental reason of today’s horrors and it became incredibly cruel after the Soviet Union was founded as a solid entity to represent ‘the alternative’. In Africa, in Middle East, Europe and in Turkey we have witnessed the bloodthirsty attack of capitalists joined by state apparatuses on the people that wanted social justice. I am thinking all those generations who lost their lives trying to tell that this zeal would bring barbarianism, as Rosa Luxemburg said once. Especially since the end of 1970s, the imposed conviction was that the free market economy would regulate the economy and politics and that all the world would end up as a collection of liberal democracies. That was a massive piece of bullshit then and now we are all seeing what bullshit ideas can do to humanity once they start to rule. The best example is Brasil at the moment. The Amazon forest is burning and we have Bolsanaro talking about sovereignty. Good luck to all the world leaders trying to convince him to be more moral. It is impossible for them to have a moral high ground because the main idea is to eat the world and humanity for the sake of profit, which stands in the very core of the global system today.

Luke: An important part of the authoritarian picture that I feel was missing from your book was China. Now obviously China has always been an authoritarian country. We are seeing now the protests in Hong Kong against Beijing. However, only relatively recently has it been a serious geopolitical rival to the USA or the EU. I wonder if having such an authoritarian country like China getting close to an equal footing with other world powers has made it easier for countries to become authoritarian or are there other ways that China fits into the picture?

Ece: I do not believe that Europe or the US needed China to have their authoritarian leaders. China is a curious place that never experienced liberal democracy nor free market economy and that is why, together with Russia, it is not in the book. However, one thing is very clear to me about China. Between the US and China, there is no longer an ideological war, but rather a practical power game. That is very different from the Cold War, in which the US represented the so-called free world and USSR was the villain of the globe. Whereas today neither the US nor Europe –after the refugee crisis- have no such moral high ground.

Luke: Your book draws a lot of its ideas from the events in Turkey over the last few decades, one of the things that is notable about the AKP era is the utter failure of the opposition parties to win elections. Sure the deck has been stacked against them, but it has taken them 20 years and a full economic meltdown to start working out how to win. I think in part that is because the CHP has its own toxic legacy and poor leadership to deal with. However, I wonder if there are any lessons opposition political parties facing authoritarian leaders can take from the Turkish oppositions’ experience?

Ece: Certainly. There is a long list of “what not to do” that can be derived from CHP’s history of last two decades. It is tragically comic that in the US and in Britain at the moment the opposition parties are committing the exact same mistakes to experience the exact same failures. This is in fact why I wrote How To Lose A Country. This is a global matter and unless we form a global solidarity there is no way out of it. Repeating the same mistakes with the illusion of “exceptionalism” will only make us lose time and political energy.

Luke: Let me tell you a story. I’ve screwed the details around to not embarrass anybody, but the sentiment is the important part. I was walking through Boğaziçi University with a friend of mine who is a conservative religious lady from an AKP family. We walk past a middle aged woman marching off somewhere. My friend leans over to me and says, “They hate that I’m here talking to you in English.”

I let the comment slide. I’m a foreigner and was aware that there might be social cues I could have missed, but I only saw a middle aged women -possibly a bit sour looking- in a rush. I didn’t want to talk about it either because I’m sure I would have got quite a defensive response.

It seems to me that part of being able to have conversations is starting to talk about victimisation. As you point out in your book, victimisation is an important part of the narrative of populism. The tricky thing about it is that sometimes it is real, sometimes it is manufactured and mostly it is a mix of both. How do we begin to dispel some of the feeling of victimhood amongst the supporters of populism without putting people on the defensive and retreating to partisan lines?

Ece: This is a big topic in How To Lose A Country. Among the supporters of right wing populist leaders there are two types of victimhood; the real and the manufactured. This goes for every country and not only Turkey. The manufactured victimhood becomes the dominant narrative on the road to power as it happened in Turkey and in the US (Mexicans are stealing the jobs) and in Brexit process (Turkey will join EU to steal our jobs etc.) Listing the facts that disprove these lies are not helping, I guess we all know this by now. So we need a different narrative to tell our shared victimhood, which is social injustice. However, I guess the opposition parties in Europe and in the U.S has been reluctant to do this as they don’t want to be considered “socialists”; a fear that has been inflicted on them during the Cold War. This is why I am following Bernie Sanders very carefully. At the moment he is the only political leader in the Western World that name the names and without any fear pointing out the real problem; accumulated capital in the hands of the few and the growing poverty. When you start talking about the real victimhood with all the truthfulness and without any hesitation, people who have the illusion of manufactured victimhood narratives would listen. I do believe in this, not because I want to, but for the simple fact that it has been so throughout modern history.

Luke: You caution against humour when confronting authoritarians. However, I think there is a tension there as you also say that authoritarians demand respect. Given that most authoritarians have pathetically thin skins. Can’t humour be an effective tool against these leaders, firstly, simply because they personally dislike being the butt of jokes and also because it pushes back against the idea that these leaders are worthy of respect?

Ece: I told the story of humor starting as an effective tool against these leaders and ending up as a cynical attitude that hurts the opposition itself. Also I tried to explain how the political humor becomes a political shelter for those who feel like “As long as we laugh we won’t be hurt by politics.” Turkey is the heaven of political humor. If it did any good, I assure you it would have brought down the palaces long ago.

Luke: Like many people in Turkey, I was happy to see the AKP lose the mayoral elections. However, I’m very suspicious of the opposition CHP. They hardly have a pretty poor history of injustice and corruption themselves. Moreover, any feeling of good will I felt towards their victory was snuffed out when Mr. İmamoğlu seemed to embrace an ugly line about Syrian refugees. Part of what I felt powerful about your books was you talked about the way that people on the left and liberals supported the AKP when it was starting out because they thought they saw an opportunity to break the power of the generals. How do we avoid repeating the same mistake now? How can we build coalitions that can beat authoritarian, populist and nationalistic leaders without simply replacing them with more of the same? Or to put it another way, how can the oppositions be popular without being populist?

Ece: Great question. Although there are assumptions in the question that I wouldn’t necessarily agree with, I must say that we must be on our guard. Politics is not about devotion, but about questioning. As far as I can see, Mr. İmamoğlu is closely watched by those people who gifted him with his political victory; namely the people who fought for him like there is no tomorrow under impossible conditions and despite the fear inflicted by the political power. And he has been open about his political doings since day one which is absolutely against the right wing populist rule book.

Luke: One of the things that I find interesting about you personally is that you straddle the world of journalism and fiction. What role, if any, can novelists play in resistance to populism and authoritarianism?

Ece: I have a very simple answer: Tell the story. Tell the story with your consciousness.

Luke: I wonder if you could recommend some books that have helped inform the ideas that ended up in the book?

Ece: That would make a bibliography that would resemble a doctoral thesis! Instead let me tell you what I am reading at the moment. Paul Mason’s Clear Bright Future, Bhaskar Sunkara’s Socialist Manifesto and anything about the post-human era which focuses on 4th industrial- digital revolution that I can get my hands on.