Amy Spangler is one of the founders and agents at Anatolia Lit an agency representing Turkish writers aboard and the Turkish rights of international authors. She is a translator who has a long list of translation credits on a range of important book. Recently her agency represented Selahattin Demirtaş’s first book Dawn (You can read our review of it here). She very kindly agreed to talk to us about about Dawn, working with Demirtaş and working as an advocate for Turkish literature.

Luke: Can you tell me why you founded Anatolia Lit agency?

Amy: I originally founded Anatolia Lit together with Dilek Akdemir. Quite naively I thought that I would be able to find Publisers for the books I wanted to translate into English. So that was my primary motivation back in 2005 when I decided to do this. It became quickly very clear to me that it was more of an illusion and wasn’t a very realistic expectation, basically. I didn’t know about the 3% back then, for example.

Luke: What does that mean exactly, the 3%?

Amy: I think now it is closer to 4%, but that is the percentage of books in English that are translated.

Luke: Really?

Amy: Yeh. So to give you an idea, in Turkey the percentage of books in translation is about 40%. In Germany, France and most of Europe it is about 30%. The percentage in English has always been very very low. Now thanks to some independent publishers that has gone up a little bit, but it is still lags woefully behind many other languages. It is interesting to see how the world hegemony is expressed in the world of publishing.

For that reason, although there were lots of things I wanted to translate, I couldn’t sell them. However, I kept at it and we also started selling Turkish rights to publishers here which is, frankly, a more realistic kind of business again because of the imbalance in terms of translation. There are are a lot of people who translate from English into Turkish. The fact of the matter is that statistically it makes more sense to sell books from English into other languages.

Luke: Ok. So why do you think it is so hard to sell Turkish language translations into English?

Amy: It’s not just Turkish. It is translation in general in English is not that common. There are a lot of factors especially with the bigger houses. One is that in the US and UK, editors don't want to make a decision without seeing a complete manuscript. Translating takes a lot of time and effort and, and can be very costly. Furthermore for a translator, if you don’t know if something is going to be published and you go to the effort of translating 300 pages, just to see it languish somewhere, it’s not something translators prefer to do. Actually, there are very few literary translators from Turkish into English. That means there is a small pool and they are going to focus on works that they know are going to be published.

One thing that is more difficult is that in English you don't have that many outside readers. So in Europe, a German publisher probably works with somebody who reads in Turkish for them and advises them and they can rely on that and from us, sample translations and synopses are enough and they can publish it in German. Then on the English language front you might be lucky enough to find an editor who can read French or German or one of the major European languages, and so they can read the full book once the French or German etc. translation comes out. In other words, this is the route to providing a complete translation without having to commission a complete English translation, if that makes sense.

Luke: What books have you found successful selling into English?

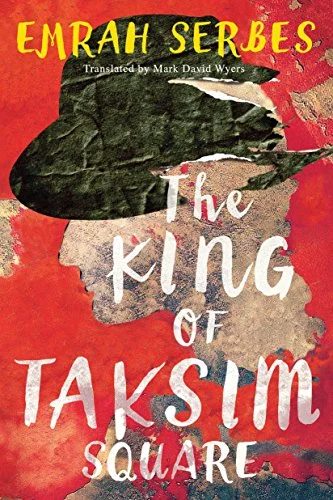

Amy: Frankly, we haven’t sold a lot of books. It has kind of ebbed and wained because I’m running a whole business at the same time. A couple of years ago, we sold English rights in a novel by Emrah Serbes, which was published by Amazon Crossing, a publishing arm of the behemoth known as Amazon, but they only publish works in translation.

Luke: Right, and thats an edited version rather than their self publishing service isn’t it.

Amy: Exactly. Its is a proper publishing house. They bough what is Deliduman (Emrah Serbes) in Turkish and published it as The King of Taksim Square. I don't care for the title, but you do what you can. So I think if you talk about this and obviously, Selahattin Demirtas’s book, they have quite obviously political edges to them. In addition to any kind of literarily merit, it helps, and I think if you look at other books that have been published in English translation, it has a bit of a political edge. I think in general for English Language there is a bit of a bias, which I hope is changing, that when they read books in translation, they are looking for a bit of anthropology. Whereas for English books or books from western Europe, it doesn’t have to be a book about that place.

Luke: It can just be a cracking novel in its own right rather than saying something about Turkey.

Amy: Exactly, so just to give you a couple of examples. The first book I translated was Asli Erdogan’s Kirmizi Pelerinli Kent, The City in Crimson Cloak. That book was published in Europe in several languages and won awards. It is a wonderful novel, very literary, but I couldn’t sell it in English because it is set in Rio de Janeiro. The response I was always met with was “why would I want to publish a Turkish author writing about Rio de Janeiro? If we want to publish a book about rio then we will publish a Brazilian author.”

Luke: Right.

Amy: So it is a bit of a double standard.

Luke: Whereas if an English language author had set a book in Rio, it probably wouldn’t have been a problem in the same way.

Amy: Exactly, so Turkish writers are put in a much smaller box. So I think with Deliduman, you had a lot of people who were interested in Gezi and what happened in Taksim square. Even though not even a third of the book takes place in Gezi, it was a selling point for us and eventually for amazon crossing. Otherwise, what we have sold to other small presses, putting aside Demirtaş for the moment because that is a much bigger press, are modern classics, which are agency is particularly strong in. So, smaller presses like City Lights, which published Yusuf Atılgan’s Motherland Hotel.

Luke: They did The Stone Buildings as well didn't they.

Amy: they did, which is by Asli Erdogan, though I don't represent her anymore. They’ve published a few Turkish authors. Bilge Karasu also comes to mind. In any case, Motherland Hotel is an amazing book it should be on everybody’s shelf.

Luke: it is a lot of fun. I really enjoyed reading that book.

Amy: It is crazy and dark and the movie’s insane too. What I like about representing modern classic especially is that they have become modern classics for a reason. In some ways they spoil you for all other books. You get very high expectations if you spend your time reading modern classics. There has been a bit of a resurgence in general in publish. There is this kind search for rediscovered, or undiscovered modern classics so that has been good for us.

Luke: You have seen Tanpinar come out in English is kind of the same way.

Amy: Yeh, it was a little early on I think. It caught on early to that wave. Sales of modern classics have been better for us in other territories rather than English so far. We also have the Sevgi Soysal novel (Noontime in Yenisehir) that I translated it was published by Milet, which is a very small publishing company based in London, but owned by someone from Turkey. They do a lot of children books, but also Turkish literature in translation. I’m trying to find a bigger publishing house to publish Sevgi Soysal. She is another writer of modern classics. We were talking before the interview about Sabahattin Ali, well Sevgi Soysa is another writer who died early, in her case from cancer at the age of 40. Before she died she put out a number of books which have become modern classics. I’m kind of hoping that a combination of interest in modern classics, increasing interest in turkey and increasing interest in women writers will help us raise the profile of writers like Sevgi Soysa and Leyla Erbil.

Luke: So are there any other Turkish writers who you feel deserve to be in translation, but haven’t got anything out there yet?

Amy: That don’t have anything out yet?

Luke: Or need more. Interpret the question however you like.

Amy: Well Leyla Erbil is one, but we are about to do a deal for a couple of her books. She was a very outspoken author, in some ways a modern classic and a contemporary author because she started writing in the 50s and her last book came out in 2013 just before her death. So her career spanned decades. She was a real modernist in style. She experimented with language. She was very sharp and into Marx and Freud when the Marxists really held Freud in disdain. She was quite ahead of her time, very smart, very well read and her fiction is infused with all the intellectual reading she did as well. So she is an amazing and very influential author. Also the first Turkish woman to be nominated for the Nobel prize for literature in turkey.

Another author we are working on is Zaven Beberyan. He is kind of the Western Armenian modern classic, the real creme de la creme. He wrote three novels in his life time and all three are amazing. Lora Sari is working on a sample translation of his novel Penniless Lovers , translating it from Armenian into English. Two of his novels have been published in French so we do have the advantage of having two complete French translations at least. Zaven Beberyan is someone we are really focusing on.

Another author I’d mention is Sait Faik, there is a wonderful selected collection A Useless Man published by Archipelago. We would love to see them do more. We are talking about that now. There is one thing about when you have somebody like Said Faik, who was a short story writer, is you do one selection and then people think that’s enough, just one selected volume. Whereas actually, there are volumes and volumes that you could translate. You could easily do a second book, or more even.

Luke: It’s the same with Yasar Kemal. His back catalog is barley touched. I think there is a slightly different problem with him in that, how do you replicate the work of Thilda Kemal and her personal relationship with him that informed her translations.

Amy: There is an authority question there that is very important.

Luke: Yeh. It makes it very difficult for someone else to step up and do that work.

Amy: I think that it happens to some degree when English publishers edit heavily, while they are translating. I started a masters thesis on this very topic, looking at and comparing translations of Mehmed Uzun’s work from Kurdish into Turkish with Tilda Kemal’s translations of Yasar Kemal’s work from Turkish into English and how the claim that both of these authors drew strongly from an oral tradition was or was not reflected in the translations. Ultimately I found in general that they were both kind of forced to fit the norms of the target language more than what was claimed to be happening in the source. So you get rid of repetitions, you combine sentences, and you make more of a “modern” novel out of it, which is something that I think Thilda Kemal did as well. She cut stuff and made it more compact and more suited to target readers expectations, which is maybe not what the original was delivering. It comes down to authority because obviously you have an author who is being translated by a brilliant and very confident translator who was also his wife so she had access to this kind of authority that I don't think other translators would. There is one thing about becoming a translator is really helping translators build up their confidence with the idea that they are rewriting something.

Luke: I hosted an event with a couple of Turkish translators, they were asking each other to what extend do you feel you have the ability to rewrite stuff. One of them said I don't feel I have that right at al, while another said what are talking about, you should be able to rewrite and edit as you go. I’m not a translator so I don't quite know where I fall on that question.

Amy: there are trends in translation just like there are trends in everything else. Right now we live in an age of domestication, rather than foreignisation.

Luke: Can you explain those terms please.

Amy: So domestication means… like I was talking about earlier with the example of Yasar Kemal, you try to mould the text towards the target language. So in this case, Turkish to English. Fluency is in right now, so editors and Publisers want something that reads smoothly. They don't want it to read like a translation. But this is a trend. It’s not always been like this.

For example, footnotes are out. Nobody wants footnotes in their Márquez anymore. As much as that might might add to an interesting reading experience.

Luke: They can be useful because there are some words that you just can’t translate easily.

Amy: Well there are words and you can think about this as a transaction. I didn’t come to this book knowing about the coup in 1970 and 60. Knowing about all these things, about class in Turkey. If you come to the text with a certain amount of knowledge about the context, it helps. If not, you can help the reader catch up in certain ways, by giving them a footnote with certain cultural references. So yes, there are words, but there is also context that is kind of essential. Sometimes you can give that well like in Demirtaş’s book there is a forward by Maurine Freely, and a preface by Demirtaş himself which helps to give a lot of context by addressing the foreign reader.

Luke: He is a bit different though because a quick google can give you a lot of information about Demirtaş.

Amy: This is true.

Luke: Luke: Shall we move onto him now?

Amy: Sure.

Luke: How did you come to represent him?

Amy: So we represent Demirtaş on behalf of Dawn’s publisher, which is Dipnot and before the book was published they asked me if I would be interested in representing it for the foreign rights. I said, “of course.” A couple of the stories had been published, but the rest of the stories hadn’t. I said I’d be happy to do it.

Luke: I was a little cynical when I saw it was coming out because it seems like an easy sell. But I was happy to see, when I read it, that the stories were good.

Amy: Yeh. I was myself concerned about the stories and the quality they would be because as much respect and love we might have for Demirtaş as a politician and he is clearly an intelligent man and a powerful speaker, it doesn’t mean that he’s good at writing stories.

Luke: Absolutely. But I can also see how selling that book could be easy. There is an obvious think piece to be written about it in the guardian “imprisoned political writes story collection.”

Amy: That makes it an easy pitch, obviously he is one of the highest profile political prisoners in Turkey, but quite a lot of imprisoned people are writing books.

Luke: Each story is kind of details a little slice of Turkish life. To what extend to you think that it represents a kind of ethical manifesto?

Amy: Not so much a manifesto, but his ethics, which inform his politics, are very much in the stories.

Luke: Right, it’s not really as political as I though it was going to be but it is very ethical.

Amy: It is quite political, some of the stories in particular. There is more of an ethical humanist viewpoint that shapes the stories.

Luke: How much do you know about his writing process?

Amy: Honestly, I don't know any more than he has told other people in the press about his process itself. He has his pen and his paper and he is writing.

Luke: And plenty of free time.

Amy: His texts go back and forth via lawyers. They go to the publishers to the editors back and forth other than I don’t know so much, like what time he gets up and starts writing.

Luke: So you dont know how he forms ideas or if he is a planner or a discovery writer.

Amy: I dont know the technical details of it. I will say, I think you can tell particularly from some of the stories. He is a lawyer and he has seen a lot of cases over the years and a lot of cases had to do with human rights and you can defiantly see them end up in both Devran, his second collection, and Dawn as well, his experience with these cases come through in these stories.

Luke: That makes sense doesn’t it. There is an honour killing story (Seher) that has that feeling about it.

Amy: there are others as well there is the young lawyer on the bus (Asuman, Look What You Have Done), the driver pulls one over him by telling him this crazy story. It’s very funny.

Luke: I’d forgotten about that one. You are right it was very funny.

Amy: In the end you find out he has become a lawyer who is handling the driver’s son’s case. And there is Nazan, the Cleaning Lady, which is my personal favourite.

Luke: Remind me which one that is.

Amy: it is the one with the cleaning woman who loves cars.

Luke: Oh yes, and she gets caught up in a protest then ends up on the front page of a newspaper.

Amy: Exactly. So obviously A letter to the Prison-reading Committee has a political side.

Luke: What I liked about it was it wasn’t really about him. I was sort of expecting the book to be about him and his life. But it wasn’t it was focusing on the ordinary lives of other people in turkey. In a kind of Orhan Kemal, Nâzım Hikmet kind of way.

So tell me about the translation process. How was that for you?

Amy: So I co-translated it with Kate Feguson. We have known each other for many years. We’ve done these translations workshops together. I know that Kate is also quite enthusiastic about Demirtaş. First of all I should say that when we first started representing Demirtaş, I didn’t expect it to take off abroad quite so quickly. When I announced we were handling it, suddenly the Italians made an offer. We had this Italian pre-empt and that’s when I thought, this really is going to be something.

Luke: I had had a feeling it was going to be something as well. I have an acquaintance who works for penguin and she was writing to me about two years ago saying I’ve heard about this Demirtaş guy. what do you know?”

Amy: Maybe I should have expected it to move quickly, but I think that in general I always find that publishing can be a slow moving industry with few exceptions. I wasn’t sure if this would be one of those exceptions.

As soon as we got the Italian offer I called Kate and said “Lets sit down and translate a sample to share with Publisers.” I had already written up a detailed synopsis and summaries of all the stories. So we sat down and I translated Nazan and she translated Seher. We sent those out. When we had eventually sold the English language rights we got to work on translating the rest of the stories. Basically what we did is divide them up, so she would do the first drafts of certain stories and I would do the first draft of other stories, then we would share them and send them to each other. She also lives here in Istanbul. So it was easy for us to get together and discus our notes.

Each one was kind of draft 1, 2, 3, and 4. Then they would go to Maureen Freely as the first reader. She came back with her notes, the UK editor had notes and the US editor had notes. There was a lot of back and forth.

Luke: Working with another translator. How did you manage to keep the language consistent? Were your styles very similar from the beginning or did you just edit them into alignment?

Amy: I think, there is something to say for being in frequent contact and we were already familiar with each other to begin with. I think one point is that I’m an American so I would sometimes use very American idiomatic expressions. Her being English she would say, “Wait I don’t get this,” or use something decidedly different. It was good to get the mid Atlantic, which is kind of controversial and not something I want to get into here. But that is what the publishers wanted so they could publish one text for both territories.

I feel like Kate and I have similar sensibilities. Also, it is easier on short stories. I think it is quite impossible to collaborate on a novel. Demirtaş is not monotone. He has quite a different voice in some stories. So it doesn’t matter which one of us is doing it, but we have to try to recreate that particular voice.

Luke: Right.

Amy: Hopefully it sounded ok.

Luke: It read very nicely. So obviously Demirtaş is a controversial figure here in Turkey. Have you received and push back for representing him.

Amy: No.

Luke: Oh, good.

Amy: You know. It is is interesting it was one of the things I was first asked was if I would be concerned about that, but it is a collection of short stories by this important figure, so it is worth any kind of risk that might be involved. I haven’t had any pushback.

Luke: Not even a bit of moaning on twitter?

Amy: well yes. Especially because the US edition was published by Sarah Jessica Parker, as part of her SJP for Hogarth imprint. So you might have seen there is a photo in vogue with her carrying the book.

Luke: I did not see that. Vogue is not in my usually reading rotation.

Amy: I mean, neither in ours. There was this photo of her coming out of a New York apartment carrying the proof, so this is before the book was yet published in English, sometime around new years. The photo started to make the rounds. There were a lot of people speculating and coming up with conspiracy theories about how this woman, this Jew -even though she is not even jewish, but is married to a jewish man- why Sarah Jessica Parker had this book. That was kind of crazy and people got wound up about it, but it never really had any direct repercussions on us. We openly share it on our webpage and social media, but I don’t go out and get unnecessarily involved in polemics over politics.

Anyway, the Sarah Jessica Parker photo was the time it got the most crazy. It wasn’t about literature. It was about politics.

Luke: That was what I was suggesting.

Amy: If you look at the Turkish press you have people criticising the book in various ways, some of it obviously politically motivated and not valid at all. I think there has to be a balance of not tearing something apart for political reasons and also approaching it as a literary work and being critical of it as such. Every book is open to criticism, as is Demirtaş’s book, but I feel like there has been a bit of an imbalance in that respect. If that makes sense.

Luke: I just have two more questions to put to you. I’m not sure if this is the kind of agency you generally are, but I know that some people are read us are aspiring poets and novelists, so I was wondering if you had any advice for pitching to agencies?

Amy: We represent several contemporary authors. So far people who write in Turkish only. We discovered them in different ways.

I will say two things here. Personally as an agent and as an agency that does accept submissions, if there are guidelines on the agencies webpage, follow the guidelines. That should be obvious, but sometimes people don’t do that. You have to keep in mind that time is precious. These things take time and for us even getting somebody to read a text and reject it is almost a success, especially if they actually tell you why they rejected it. That’s valuable information, and at least you know it has got some attention. You have to remember that editors and agents just receive so many submissions.

Luke: I know how it is from both sides of the short story grinder.

Amy: They keep coming.

Luke: Even in my reliably humble publication you get people who don’t read the submissions guidelines. And I mean why? It’s right there.

Amy: It’s quite straightforward and there are deadlines there, you need a synopsis and the first couple of chapters. Whatever it is. It is fine to get back to somebody if you don’t hear from them, but if it has only been a week, its because they have a lot to do.

Another thing is don't come to me to tell me about your book, or don’t try to insist on coming to the office. Send me your materials. We can look at it and decide if it makes sense or not. I find it particularly irritating when people insist, saying, “I want to tell you about my wonderful book.” Send me your work them if we need to talk, we can talk.

The other thing is to try and know who you are submitting to. Just getting a literary agent doesn’t get you anything if it isn’t the right agency. Whoever you like, or whoever you are influenced by, find out who their agent is and try them or try that editor if they are accepting submissions. All agencies are not created equal int he sense that there is a variety. If I don't know anything about fantasy, it doesn’t make any sense to pitch me the book. It doesn’t make sense anyway because I’m not going to know the right editors.

So look up authors who you like and look up to and maybe try to reach them.

Luke: My last question is could you recommend three Turkish books to our readers?

Amy: That’s tough. I'll have to try and not be biased and recommend my own stuff! One that we mentioned earlier Sait Faik A Useless Man is on the list. We’ve talked enough about Demirtaş we don’t need to put him on the list. Gülten Akın’s poetry collection 42 Days and Other Works. I’m going to say Sevgi Soysal because I love her so much.